Bonedigger, Bonedigger — How Grace Land and Saint Monday are Building an Empire in London

Andreas Akerlund is hard to miss. Tall, bearded and with grey-brown locks swept defiantly back from a balding pate, the Swedish co-owner of London pub group Grace Land stands out in a crowd. If you’ve been to one of the capital’s bigger beer festivals you’ll probably have spotted him, glass in hand, politely listening to the entreaties of brewery sales representatives.

Photography by Lily Waite

He prefers, though, to blend into the background. Andreas, who came to London as a teenager, dresses almost invariably in black—t-shirts, hoodies, jeans—and not just because he loves music that runs the gamut from “heavy” to “doom”. He doesn’t like to be photographed. He enjoys chatting, but not generally about himself, and he is not boastful. He is resolutely unflashy, with the notable exception of a large skull-shaped ring that he wears on the second finger of his right hand. “I really should grow up soon,” the 52-year-old says when I ask about it.

It’s this undemonstrative nature, perhaps, that explains why his key role in modern London beer is so under-appreciated. He has been, variously, co-founder of Barworks, whose dozen-or-so pubs were essential addresses during craft beer’s boom years; champion of quality beer since the 1990s, when he put Freedom, London’s first modern lager brewery, on the bar at the Hoxton Square Bar and Kitchen; start-up investor and director in Camden Town, one of the city’s game-changing breweries, in 2010; and co-owner with Anselm Chatwin of Grace Land, whose six pubs are amongst London’s best for drinking beer.

“Andreas and Anselm have been pivotal in many London breweries’ success,” says Jack Hobday, co-owner of South London brewery Anspach & Hobday. “They’ve shown tremendous foresight over the years; by embracing modern beer they’ve established new norms for what a London pub can offer.”

Now there’s Saint Monday, a brewery and bar opened by Grace Land in London Fields, Hackney in September. A new brewery, in this economy? They once sprouted in East London like weeds beside the Regents Canal—but with craft brewing on the retreat in London, battered by Covid-19 and multinational monopolisation of bar tops, it is an eyebrow-raising move.

Local omens are not necessarily promising, either: London Fields Brewery, previous occupants of Saint Monday’s site, never really took flight despite early hype and, later, oodles of Carlsberg money. Some astute observers felt the site—tucked away between Mare Street and London Fields, with no outdoor space—had much to do with that.

Andreas, though, has backed enough winners over the past 30 years, most recently in tandem with Anselm, to be taken seriously and perhaps the moment is right. There are signs that London’s long post-Covid languor is beginning to lift, with the rate of closures slowing and some confidence gradually seeping back into the city’s battered hospitality sector. Could Saint Monday, like Camden Town and Barworks before it, be just what London’s beer scene is looking for right now?

***

When the first Covid-19 lockdown began in March 2020, Anselm and Andreas were in very different places. Anselm was lying in bed with Covid, feeling like he was at death’s door, incapacitated for two weeks, and Andreas was stranded in a Swiss ski resort, strapping skins to the bottom of his skis to hike up mountains after lockdown shut the lifts.

It has become a cliche to suggest that Covid changed everything, but for Grace Land it really did. Andreas had already begun to do more before the pandemic, he says, but it was Covid that made him switch to full-time. Operations manager Sam Weston went on furlough and then left, leaving Anselm, even when recovered from Covid, with too much on his plate. Andreas, back from his Swiss jaunt, stepped in. “We became much more hands-on,” Anselm says.

But there was push as well as pull. In October 2021, Barworks sold 13 pubs to Urban Pubs & Bars, fundamentally changing the business. Over the previous 10 years, it had become more and more craft beer-focused, exemplified by pubs like The Exmouth Arms in Exmouth Market and the Well & Bucket in Bethnal Green Road. Since the sale, it has focused on bigger venues like the Mare Street Market brand, the first of which is a few hundred yards from Saint Monday.

This approach is clearly not how Akerlund, for many years drinks buyer for Barworks, would have chosen to do it, although he’s too diplomatic to say. Conflict is not his thing. He doesn't have a role with Barworks anymore, beyond twice-a-year board meetings; the business is now run by Marc Francis-Baum, with the other founder, Patrik Franzen, also having taken a back seat.

The drift away from Barworks was a long-term process.

“It wasn’t a one-day-to-the-next sort of thing that happened; it’s been going on for ten years,” he says. “It was gradually happening, and I was looking for more to do. Marc was really keen to do bigger venues, like Mare Street Market, and I’m more comfortable with pubs. It was a big part of my life, but I’ve moved on.”

““In every Grace Land pub I know I’ll be able to choose from a great beer list, be served by good staff, in a nice atmosphere full of local people to that area. They’re great places.” ”

Does he miss the pubs? (When I posted a picture of the unused handpumps at The Well and Bucket on Instagram in December, he sent me a crying emoji.)

“It was necessary, and it was a good deal for everybody around the table,” he says. “It’s a bit upsetting when I go past The Griffin or the Three Johns, but you get over that.”

Business partners, of course, often drift apart. There doesn’t seem too much risk of that, at the moment at least, with Andreas and Anselm. The latter has a similar approach to life, from a passion for black jeans to a predilection for large families: Anselm has four children, Andreas five.

“There are things that we don’t agree about, but they’re fine details,” says Anselm. “We have quite a strong [shared] idea of what we want to do generally.”

They met when Anselm took a job as a bar back at Two Floors, Barworks’ bar in Soho, whilst he was at St Martin’s College (now Central St Martins) in the early 2000s. Temperamentally similar and with a shared passion for music, they cooked up a vague plan to open a dive bar/gig venue—and when a site, formerly The Camden Tup, came on the market in 2009 they opened the first Grace Land venue, The Black Heart.

It wasn’t an immediate success. “The Black Heart was a dismal failure for many years,” he says. “But it’s about working with the concept, sticking with it. People get it now.”

That philosophy has served them well in the years since, during which they’ve slowly accrued a small family of high-quality pubs: The Earl of Essex in Islington, The King’s Arms and the Bethnal Green Tavern in Bethnal Green, Red Hand in Dalston, and The Axe in Stoke Newington.

There have been missteps. The Mermaid in Clapton opened in 2016 and was sold not long after, and Earl’s, a brewery squeezed into The Earl of Essex (whose brewhouse became Newbarns Brewery’s first brew kit, and then was split between Dundee’s Holy Goat Brewing and Cornwall’s Ideal Day Family Brewery) during the brewery boom of 2014, was never a good idea in such a small space. By and large, though, what they’ve tried has succeeded.

It’s made them a central part of London’s beer culture, to the extent that they’ve employed many of its more interesting characters over the years: people like Mauritz Borg, bar manager at The Kernel’s taproom, who worked at The King’s Arms in 2016 and then The Axe from 2017 to 2019.

“I loved working for Grace Land,” Mauritz says. “Having worked for other craft-beer focused bar companies [Draft House & BrewDog], Grace Land was easily the best. I like that Anselm is still hands on and cares about the sites and is friendly and respectful, while giving room to staff to shine if they have good ideas.”

Not every former staff member, presumably, will be as effusive about Grace Land as Mauritz, who has positivity running in his veins—but it’s telling that he still goes to the pubs as a customer.

“In every Grace Land pub I know I'll be able to choose from a great beer list, be served by good staff, in a nice atmosphere full of local people to that area. They're great places.”

They’re also, for the main part, clearly pubs, albeit at the smarter end of the scale. That has most to do with Anselm, whose focus has always been on Grace Land and whose aesthetic was honed at St Martin’s. Andreas has, courtesy of Barworks’ success, been able to focus on other things, from the East London Liquor Company to his involvement in the founding of Camden Town Brewery.

That came about through Camden founder Jasper Cuppaidge’s wife Laila, who was a customer at Two Floors in Soho in the early 2000s. “We were introduced and we’ve been really good friends since,” Andreas says.

It’s a relationship that demonstrates how his interest in beer has grown. “At that time I was absorbing knowledge from a lot of the people we were working with, and [we were] always trying to be different from the bar next door. It’s about being open, about not only going for the money and the easy choices.”

“When we opened the Hoxton Square Bar and Kitchen in 1997, we started off with Red Stripe and Guinness—but very soon after that we had Paulaner and Affligem, which was quite out there then. We took Guinness out and put Freedom on when they started doing the stout. We had Sam Smiths and Brooklyn in bottle.”

He has repaid this education in advice to London brewers, according to Jack Hobday.

“Andreas was one of our earliest patrons and he suggested, back when he was involved at Barworks, that we should do a nitro version of The Porter,” says Jack, whose London Black nitro porter has become a phenomenon over the past few years, now accounting for more than 70 percent of the brewery’s sales. “We should have listened earlier!”

Some things took longer to learn about than others, according to Anselm—such as cask ale. “I gradually learnt more about beer as the years went on, but when Jasper opened The Horseshoe [in 2006], for example, he was doing cask and I wasn’t sure—I hadn’t got to cask on my beer journey then.”

Cuppaidge, of course, is no longer at Camden; part of the motivation for Grace Land to replace Camden Hells as their house beer earlier this year. Deliciously, it gave way to Lost & Grounded, the Bristol brewery run by former Camden head brewer Alex Troncoso and Annie Clements, whose time in North London ended with a certain amount of ill-feeling; they didn’t see eye-to-eye with Cuppaidge. The process itself left some lager-brewing noses out of joint—other breweries from London and elsewhere were in the running—but for Andreas and Anselm the decision came down to two things: quality and price. Lost & Grounded won on both.

“I think we sell more of the house lager now it’s changed,” says Anselm. “We’ve won back some of that craft beer crowd, too, because people respect Alex so much.”

It’s not personal. How could it be? Camden Town’s sale to AB InBev in 2015 made Andreas rich, without dimming his passion for hospitality. It might have changed him in one way, though.

“I think I’m much easier to get on with than I used to be,” he says.

Anselm, listening, cackles with laughter: “Oh a gazillion times easier.”

“I guess that’s [getting] older and wiser, or whatever you call it.”

It’s hard to know sometimes if Andreas is being flippant or not: he’s obviously keen not to reveal too much of himself.

“I used to be the Bad Cop and now I’m the Good Cop—he’s taken the Bad Cop role,” he says, laughing, pointing at Anselm. Both are motivated by the next thing, motivated enough for Andreas to be out late on a Friday evening fulfilling his role, as Anselm puts it, as “head of maintenance”.

“Do you know how many texts I get on Friday nights about blocked toilets, or dishwashers not working, or leaks from upstairs neighbours?” Andreas says. “But it’s not difficult. It’s actually quite fun.”

***

The various strands of Hackney life come together, after a fashion, on Mare Street. Running almost directly south from Hackney Central Station to the Regents Canal, it is home to a branch of Primark and to he Cock Tavern, to Mare Street Market and the Hackney Empire. There are nail salons and charity shops, a 17th-century merchant's house and plenty of nondescript newbuilds. There is The Dolphin—“London’s most notorious party pub”—and the Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities.

It’s clear which part of Hackney’s varied community is growing, though. Looking up Mentmore Terrace from the door of Saint Monday, there is a string of recently constructed blocks of flats. The closest, The Laundry (where the hoardings promise that “A Life in LONDON FIELDS is a life full of COLOUR and CHARACTER”), is set to open next Spring, with one-bed options starting at £630,000 a pop.

This is presumably good news for Saint Monday, which has plenty of both COLOUR and CHARACTER. Take the 16 tap handles, for example. Each is different; some have skulls, others are mostly metal, all of them look essentially like repurposed tools of one kind or another.

They’re a good example of how Anselm and Andreas dovetail when it comes to decision making. “I chose three and Andreas picked the rest,” Anselm told me when I visited, challenging me to guess who picked which ones.

I couldn’t, but there’s plenty else to divine from looking at them. There’s a tidiness to their near uniformity that reflects how the pair do things (Anselm hates American-style tap handles, he says; they’re messy), a tidiness reflected in the rest of the Saint Monday taproom. One wall is given over to posters for gigs at the Black Heart (or elsewhere, promoted by former company of the pair), an artfully arranged blend of styles and band names: Wallowing, Wren, Lingua Ignota, Bongzilla. Chains hang down over the entrance to the corridor leading to the toilets.

This is a bar rather than a taproom, a very deliberate decision. The tables and the bar are copper; Anselm fusses about the distressed finish on the bar’s front, which is not quite how he’d envisaged it. Branding is subtle to the point of near invisibility. There's a red-lit wall lamp outside, and a logo on a flag in the corner of the bar, designed by long-time Grace Land collaborator Bonnie Barker, featuring a crescent moon, stars and what looks like a brain with flames coming out of it. Outdoor space has been carved out of the front section, rectifying one of the site’s key problems in its London Fields days.

Then there’s the (almost) floor-to-ceiling glass that separates bar from brewery, about the last thing that remains from this place’s London Fields days. Much has changed in just a few months but, given the annual rent payable to landlords The Arch Company (£97,998 for this site, and £41,200 more for Mentmore Street, a warehouse space five minutes’ walk away), that’s understandable.

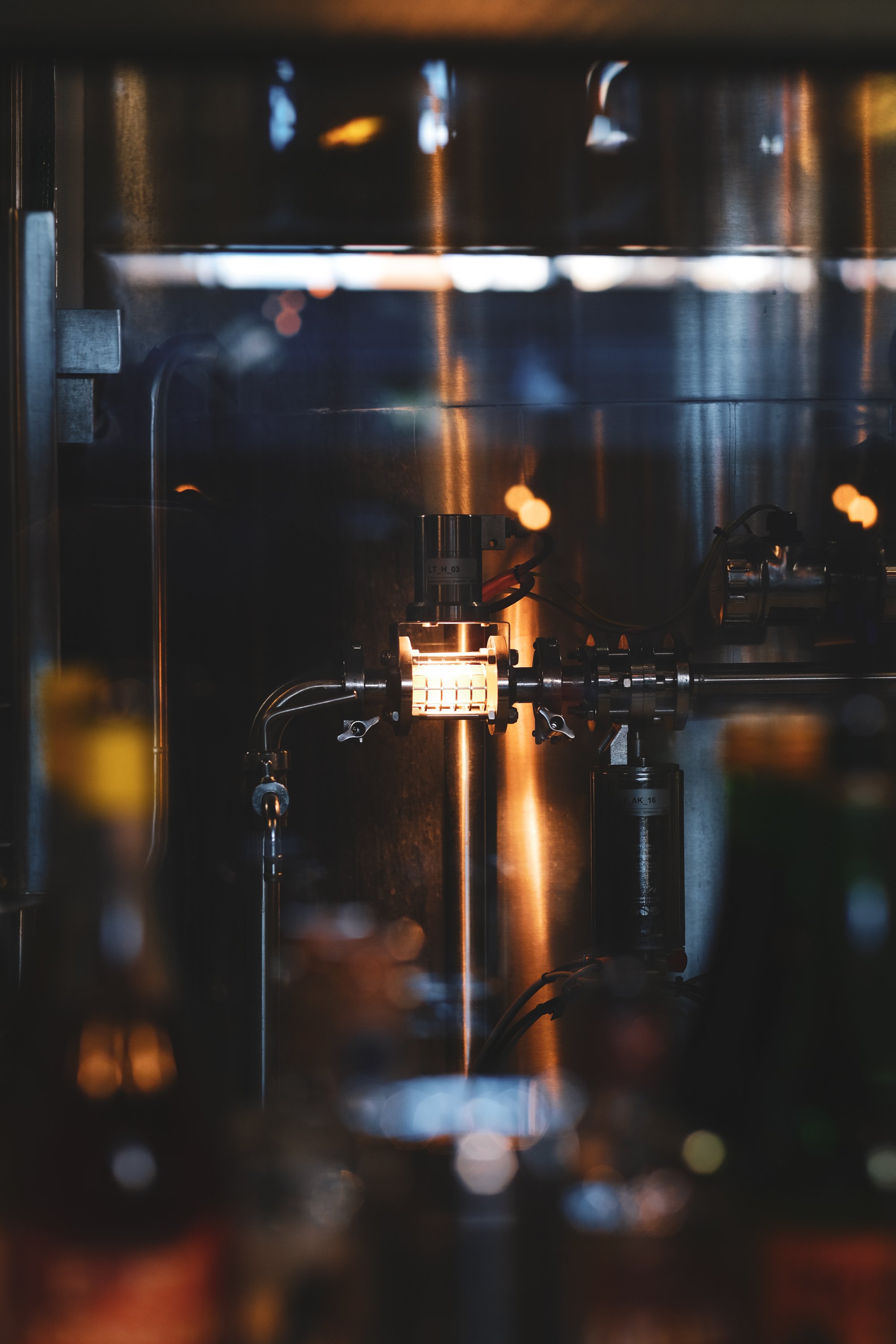

If the rent is eye-watering, though, the price paid for the brewery—£400,000, compared to what it was originally marketed for—represents an excellent deal. For that they’ve got acres of glimmering stainless steel, including a 15-hl brewing system made by Kaspar Schulz in Bamberg, a compressed-air machine from Airbox Center, a canning line from Cask Global, and more besides, including a floor paved with the industry’s finest mosaic tiles, provided by Kemtile. All this cost Carlsberg more than £2m in 2019. It’s far beyond what most new breweries can dream of.

The brewer in charge of all this is Mark Walewski, formerly of Beavertown, Brew By Numbers, Denmark’s Alefarm, and Mikkeller’s London brewpub. He leads a three-man team, producing (at the moment) eight different beers, from Pilsner to Baltic Porter, starting at £6 a pint. They’re not to capacity at the moment, he says, which means they have space to do some contract brewing

““It’s new to us to have a brewery, it’s exciting. It’s really hard for us to go back to somewhere like The Earl of Essex—which is having a record year, it’s doing really well—it’s hard for us to get motivated by that.””

There’s still plenty to iron out. Of the beers I try, the pale ale is excellent, but others are not quite there, particularly an American pale ale. It’s muted, lacking zip, its New-World hop character pallid rather than punchy. It’s not down to the brewing team or the brewery itself, Anselm says, but the serving equipment.

“Beer from these tanks doesn’t taste as good as it does from kegs in our pubs,” Anselm says, casting a brief baleful glance in the direction of three 500-litre serving vessels suspended above Saint Monday’s bar. “Mark has a theory that it’s because it comes directly from a very cold fermenter into a very cold tank.”

That’s a problem? “It might be, right? That’s the only real difference from the kegs.”

Andreas: “We’ll figure it out.” He suggests I go and try it at the Bethnal Green Tavern, 20 minutes’ walk away, to compare. He’s right—it’s much better there.

***

Outside Saint Monday, London rumbles on. Corroborating evidence is scant, but it feels like the city is belatedly emerging from the aftermath of Covid-19.

“We’re getting back into a pattern [of busy and not so busy times],” says Andreas, referring to the way in which the pattern of hospitality life—much busier on Friday nights than Tuesdays, for example—has been upended by the pandemic.

They are clearly optimists. “I don’t think people have changed that fundamentally,” Anselm adds. “They still want to have a good time, and to experience quality. It’s just about whether they can afford to.”

Another pub is in the offing, but they’re reaching the stage at which they will need to employ someone else to help them.

“When we want to go to the next stage and take on a couple more pubs, that will change things,” Andreas says. “That will change how we work.”

Just like it did at Barworks—but they’re both too addicted to the next thing to worry too much about that.

“That’s the exciting thing about Saint Monday: it’s new to us to have a brewery, it’s exciting,” Anselm says. “It’s really hard for us to go back to somewhere like The Earl of Essex—which is having a record year, it’s doing really well—it’s hard for us to get motivated by that.”

Novelty isn’t the only motivation, though. For two reasonably reserved men, hospitality doesn’t seem an obvious choice of career. So why do they do what they do? Why not find something a little less conspicuous? It turns out I’m looking at it the wrong way.

“Being behind a bar is super exciting,” Andreas says, his skull ring glinting in the sunlight flooding through the bar’s black-framed windows. “I’m maybe not the most outgoing, but when you’re behind a bar it’s a bit different isn’t it? You’re almost in a stage show. You’re playing someone else.”

Beneath the black t-shirts, it appears, beats the heart of a showman. Just not one who always has to be centre stage.