The Circle is Now Complete — White Peak Distillery in Ambergate, Derbyshire

The River Derwent meets the village of Ambergate at a glide. Coursing down from its source in the peat-covered Howden Moors at the northern end of the Peak District, by the time it reaches this sleepy corner of Derbyshire it feels calm and collected. Almost statesmanlike.

Photography by Matthew Curtis

“I always envisaged this distillery, when it got built, was going to be on a river,” Max Vaughan tells me. He and wife Claire were born here, went to school here, and met here. 13 years living in North London’s Muswell Hill and three kids later, they returned, but had no intention of settling down—at least not in the conventional sense.

Instead, Max, now in his mid-50s, decided to pursue a lifelong dream, fuelled by a love for Scotch whisky, a passion passed on to him by his father. Together, he and Claire drew up a list of three non-negotiable criteria for their own nascent distillery: that it would be in Derbyshire, that it would be next to a river, and that it would be within a building with plenty of personality—something with a story to tell.

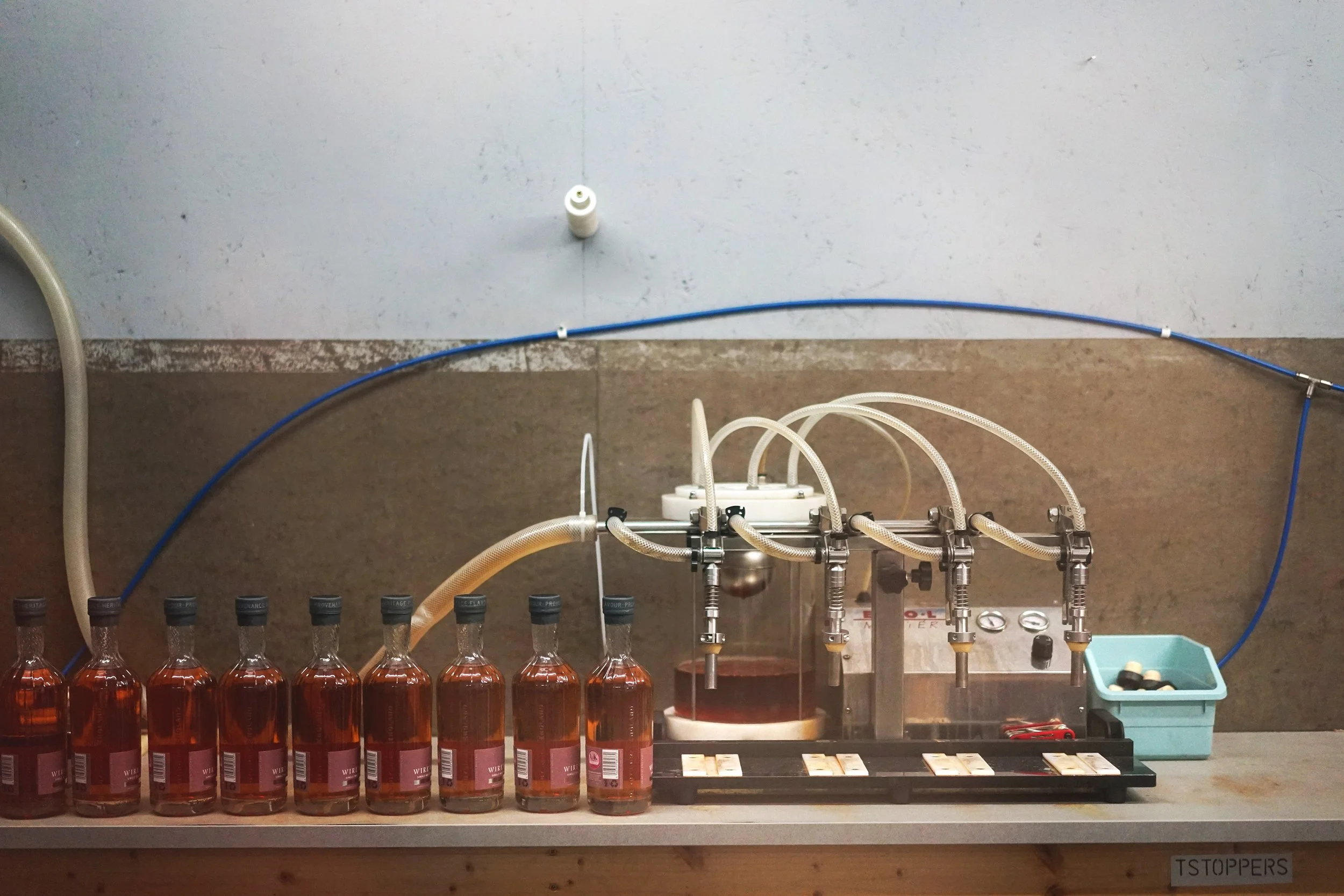

In 2016, after leaving London behind them, they would find a derelict, late 19th Century wire works nestled alongside the Derwent. Partially hidden from view by several acres of deciduous woodland, the pair of interconnected red brick industrial buildings provided an ample 5,000 square feet for the distillery itself, plus a further 30,000 for a bonded warehouse in which to store maturing whisky. Requiring a reported investment of around £1.4 million, when completed the project gave Derbyshire its first ever producer of single malt whisky. Nothing was to be outsourced, with everything, from production to bottling all taking place right here, within this building, brimming with personality.

“I remember one day, we were walking around, feeling slightly overwhelmed, and Max turned to me and said: ‘We just have to do one thing at a time, and we’ll get there.’ And he was right,” Claire Vaughan tells me. “Now, instead of walking through empty, decaying warehouses, we’re surrounded by rows of fantastic smelling casks of Wire Works whisky.”

After commissioning the distillery in 2018, and what I can only imagine must have been four painstakingly-long years, White Peak Distillery launched its first whisky under its Wire Works brand in 2022. A vatted single malt matured in both ex-bourbon and shaved, toasted and re-charred (STR) wine casks, Caduro was—and remains—an expression that represents not just the scope of Max and Claire’s intent, but White Peak’s immense potential.

Showcasing defined, yet well-balanced notes of toffee apple, freshly zested lemon, and just a whisper of peat smoke—something of a signature at the end of White Peak’s ledger—it quickly garnered attention from the whisky world. Caduro picked up a gold medal at the 2023 International Wine and Spirit Competition, and another at the World Whisky Masters in 2024. It has since taken its rightful place as the first of the distillery’s core bottlings, all of which are available year-round.

“ “I didn’t want to get to 70 and look back in anger and think, ‘I wish I’d given that a go’.””

As of May 2025, around 2,700 barrels are in-situ at White Peak Distillery. It has since added a second core bottling, a full maturation ex-bourbon barrel English single malt, alongside its Shining Cliff Gin and White Peak Rum. It also regularly releases limited, often more experimental whisky bottlings, from a full port barrel finish, to showcasing heritage barley varieties, and even collaborations with local breweries for which barrels have been swapped and shared. It was on hearing about the latter that I decided to visit White Peak and meet Max and Claire, before leaving with a sense this might be one of the most exciting distilling projects in the country—full stop.

“I didn’t want to get to 70 and look back in anger and think, ‘I wish I’d given that a go’,” Max says. “Claire and I thought, ‘Look, let’s either get on with this, or let's just shutter this dream up forever.’ And so we took the decision to get on with it.”

***

I’m keen to find out what gets Max out of bed in the morning, and how he intends to maintain a point of difference between White Peak and the 60 other English whisky distilleries that have opened since the country's first (the aptly named English Whisky Company) launched in 2006. The answer, which initially takes me by surprise but soon makes perfect sense, stems not from whisky, but from beer.

“One of the things that's been prevalent in this region for hundreds of years is beer making,” Max says. “In beer you’ve seen a massive explosion in variety and flavour, and we thought, well, there’s an approach that would make sense in single malt whisky.”

Before newly made spirit (imaginatively referred to by distillers as ‘new make’) is matured for the legally-required minimum three years in oak that’s required for it to be classified as whisky, it must first be brewed. Produced in more-or-less exactly the same way as beer, although without the addition of hops, a distiller’s wash is the initial stage of whisky making. Mashed with malted barley, and then open fermented to a strength of around 8% ABV, its alcohol content is then ramped up significantly by the distillation process. Max explains how he felt focusing on the brewing process would enable White Peak to produce a spirit that set it apart from its competitors. But to enable this, first he needed to find a brewery willing to take a gamble on a completely unknown whisky maker.

A 30-minute drive northwest from Ambergate is Bakewell, home to Thornbridge Brewery—one of the most well-regarded modern breweries in the UK. White Peak approached Thornbridge to ask if they could take some of its freshly cropped brewers yeast and use it to ferment their wash. Thankfully they were, at the very least, prepared to accommodate them “now and again,” as Max tells me. Fast forward, and every drop of whisky the distillery has released to date uses this yeast. It has become a key component in the makeup of Wire Works whisky, not just in terms of flavour, but an essential part of the brand’s identity. Thornbridge’s willingness to cooperate has provided the anchor to Max’s desire for his spirit to be connected to Derbyshire’s brewing heritage.

“Initially we were a little wary as we didn’t know what the quality of the spirit was going to be like. We wouldn’t want our name associated with an inferior product,” Thornbridge production director Rob Lovatt tells me. “However, after tasting the initial few washes we knew they were onto a winner.”

By using live brewers’ yeast, opposed to dry yeast sourced from a laboratory, White Peak is looking to extract as much flavour as possible from their wash, both via their mashing techniques—to give the yeast plenty to go at—and via the fermentation itself. Here the latter is an unusually long 144 hour open fermentation, unlike a more traditional distillery, which would look to ferment for around 48 to 60 hours.

This is to encourage as much ester production from the yeast as possible, imbuing the new make spirit with a soft, stone fruit character reminiscent of ripe peaches and apricots. Additionally, the open nature of the fermentation aims to capture some bacterial fermentation in order to maximise the citrus and tropical fruit flavours—lemon zest and fresh pineapple—in the wash ahead of distillation.

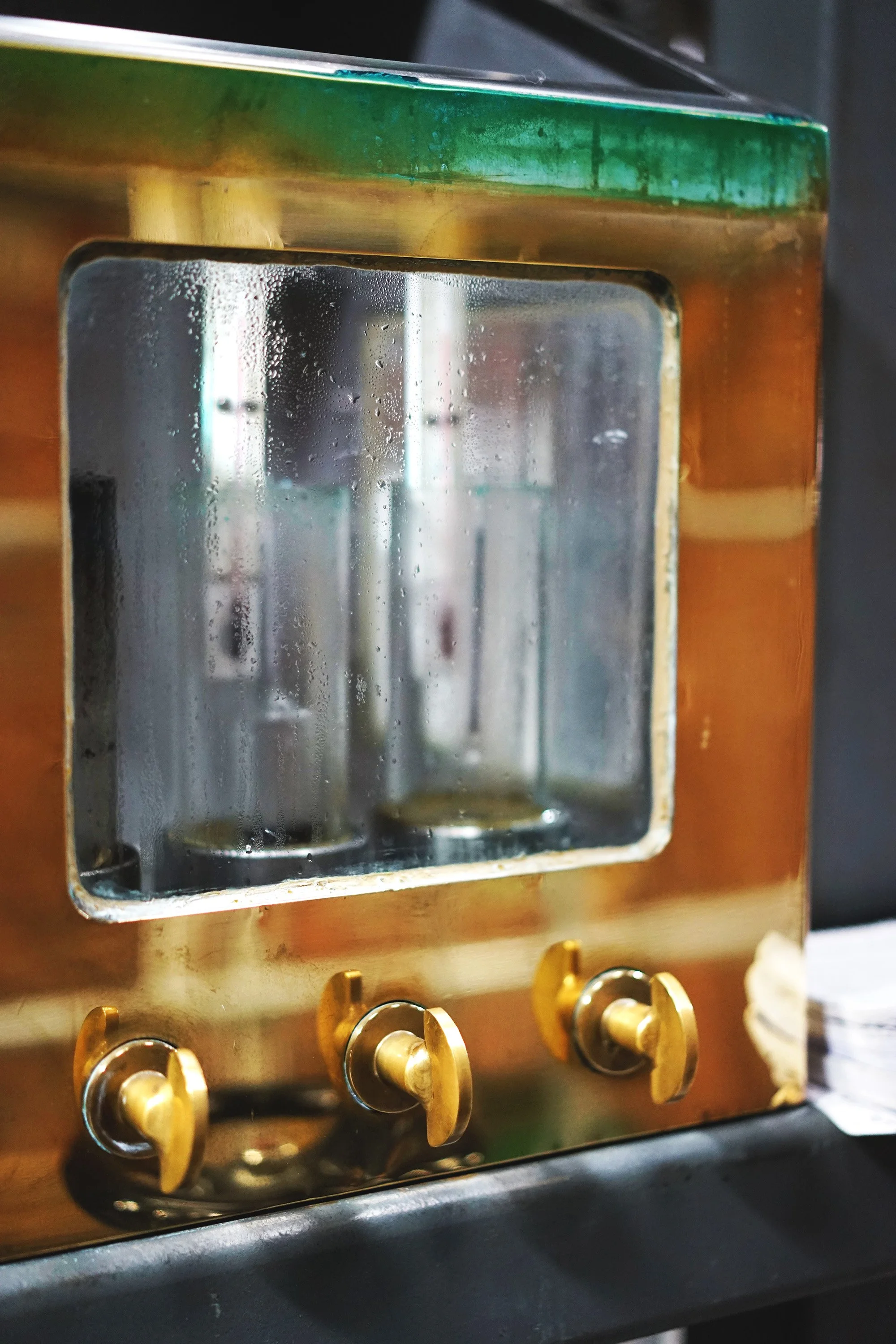

Essentially, the aim is to create a wash packed with character that’s carried through into the new make spirit. Expressed in the simplest terms, distillation is the process of heating the wash until the ethanol evaporates, where it's condensed and collected. This collected spirit, or distillate, is then split into three parts, affectionately referred to as ‘heads’, ‘hearts’ and ‘tails’. This refers to the kind of alcohol collected during the process, with the hearts being the most desirable of the three—whereas the heads contain undesirable alcohols like methanol, and the tails unpleasant flavours and heavier alcohols.

In a typical day at White Peak they’ll produce enough new make to fill two oak casks—each holding approximately 200 litres of spirit. Fortuitously, on my visit I arrive at the still while the hearts are being collected, and am encouraged to give this neat, roughly 60% ABV spirit a taste. Despite its strength, the rich, fruit character is plainly evident: intense, and slightly acidic, like the condensed juice that collects at the bottom of canned pineapple.

It’s remarkable that this won’t even get to be called whisky for three years, and most likely won’t see the light of day again for at least five. But this reminds me again how intentful and considered this all feels. This isn’t some vanity project. With its Wire Works whisky, White Peak means business.

“What we’re trying to produce is really good, interesting, flavoursome whisky, at a scale we’re comfortable with,” Max says. “Using this live yeast—although it’s not as efficient—that’s ok because the endgame isn’t about volume. It’s about flavour.”

***

Ambergate is situated between the city of Derby to the south, and the town of Matlock to its north west, right on the edge of the Peak District National Park. The Peaks see around 13 million visitors a year, which is why, at the distillery’s entrance, you’ll find a smart, well-equipped shop and visitors’ centre. Tours and tastings are held from Thursday to Saturday, while regular customers are invited to bring back their empty bottles and make use of the refilling station at White Peak’s entrance.

“We are remote, and part of that is the function of needing a lot of space,” Max says. “But there’s also that prospect of having reasonable visitor footfall because people are coming here anyway.”

White Peak’s whisky ambassador, Tom Lindsey, gives me a look inside the barrel store, reassuring me that the black patches clinging to some of the internal brickwork isn’t mould. Rather, it’s Baudoinia compniacensis or “whisky fungus” which thrives within high-alcohol environments. As the whisky evaporates from the couple of thousand stacked white oak barrels stored here—most branded with White Peak’s livery—the fungus silently basks in the presence of what distillers refer to as ‘the angel’s share’—the portion of spirit in each barrel that evaporates during maturation.

But I can’t help noticing that not all of the casks present are showing home team colours, with several of them featuring the initials NSD in chunky black lettering on their heads. Tom explains that these are filled with bourbon that has been aged for six years in Kentucky, before being shipped to the UK, where it spends an additional year maturing in Derbyshire’s far cooler climate. Although they’re stored here, and the resulting whisky is bottled here, these particular casks aren’t a product of White Peak, instead being the property of bourbon brand Never Say Die.

Max explains how this fortuitous relationship came about through an old friend from his time in North London, Nathan Dawes of N10 Bourbons. He was happy to help the fledgling Never Say Die find the English home desired to supply it with a unique selling point. Despite giving up valuable warehouse space, and time to package and ship the bourbon on Never Say Die’s behalf, this relationship fortuitously gives White Peak access to some of the freshest bourbon barrels on the market. Once emptied, they’re immediately filled with new make, and in a few years’ time the results of this collaboration, like with Thornbridge before it, will finally be showcased.

“Max was buying barrels from Heaven Hill distillery here in Kentucky, disassembling them, throwing them on shipping containers, reassembling those barrels and then putting his English single malt in them,” Never Say Die co-founder Brian Luftman tells me. “When we told him we were going to be sending full barrels over, and bottling them over there, he was like: ‘Can I have the empty barrels?’ That was gold to him.”

Ex-bourbon casks make up a large majority of the barrel store. Max explains how these casks impart less flavour than, say, a port or Madeira cask, allowing more of the distillery's house character to be presented to the drinker—hugely important for White Peak, when so much of that character is created during mashing and fermentation. These bourbon barrels are not here in isolation, with more unusual casks including everything from smaller quarter casks, to ex-Amarone, Moscatel, and even virgin English oak present. There are even barrels with a custom char level, adding smoke as a further tool within the distillery’s arsenal of flavours.

“Part of that is almost discovering what works well with our spirit, because we’re still learning stuff every week,” Max says. “It’s one of the lovely things about whisky—it can’t be rushed. It’s also one of the challenges—the feedback loop is extremely long.”

***

Those with experience will know that while any distillery tour is fascinating, the best part is the tasting. At White Peak, Max leads with Caduro (plus a taste of a freshly emptied cask of Never Say Die bourbon for good measure—cinnamon, coconut, molasses) before we sample some of its other recent bottlings.

He opts to pour what has become Wire Works’ second core-bottling, a fully ex-bourbon maturation that pours lighter in colour than Caduro—gleaming brass compared to burnished copper. It’s got plenty of heft at a strength of 53.4%, but what I’m struck by is how easily it drinks. This does not require the assistance of water, or ice, unless you wish it—and having since experimented with both, I agree with Max and Claire that Wire Works whiskies are all best enjoyed neat.

““It’s still a relatively young spirit category, with only 20 years of modern production behind us, and what it actually ‘is’ is still settling down.””

This particular batch was matured in those casks from Heaven Hill distillery, and is a superb way of demonstrating just how much work goes into the base spirit itself. Fresh pineapple and toasted coconut is tempered slightly by a feather-touch of peat smoke—that distinctive Wire Works signature. It, like everything I have tried from this distillery, showcases a quality belying the relatively short time White Peak has been making whisky.

“Cask selection has to suit your spirit, but it's the next part of the process, not the only part of the process,” Max explains, as we talk about what’s next for White Peak, and indeed, English Whisky as a whole.

In February 2025 the English Whisky Guild—of which White Peak is one of its 45 members—formally submitted its application to have English single malt whisky certified with Geographical Indicator (GI) status. Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish whisky has each held a GI for a long time. Perhaps unsurprisingly there has been some dissent, notably from members of the Scottish Whisky Association, itself bound by some of the tightest regulations in the spirits industry, thanks to its own GI. The paper, (currently under public consultation as this feature goes to press,) will be reviewed later in 2025.

“I think it’s too early to start putting rules in place that restrict how English whisky is made,” Billy Abbott, author of The Philosophy of Whisky and ambassador for spirits retailer The Whisky Exchange tells me. He also reveals his own adoration for what’s happening at White Peak, and even admits to having his own 20 litre white oak cask within its barrel store he’s looking forward to checking in on soon.

“It’s still a relatively young spirit category, with only 20 years of modern production behind us, and what it actually ‘is’ is still settling down,” he continues. “At the same time, I understand the push from the more mature companies to start defining what it is they do, to help them protect their investments and help cement consumer expectations of English whisky.”

Perhaps that youthfulness, and its inherent flexibility, is a strength, not a weakness for the English whisky category. White Peak certainly doesn’t seem to define itself any particularly rigid standards, whether that’s by putting its mark on its new make through various mashing and fermentation procedures, or how it approaches the maturation and vatting of its whisky to-be. Some of which, excitingly, has been produced using barley cultivated exclusively within Derbyshire.

After harvest, that barley was sent to Warminster Maltings in Wiltshire, where it was traditionally floor-malted. Max explains how the whole point of using this ingredient is to amplify its flavour and character in a way so that the whisky it eventually becomes stands apart from the rest of the Wire Works range. As such, the wash was produced using different mashing techniques than usual, so that the distinctive flavour of the barley shines through in the final product.

It’s an exciting prospect—a Derbyshire single malt whisky, made entirely using barley grown in the county, deliberately mashed, fermented, distilled and matured in a way that feels like more than simply a showcase of intent. When I arrived at White Peak distillery, I was certainly curious, but I wasn’t expecting the scope of Max and Claire’s ambition to have manifested in a way that would make me feel completely differently about the potential of English whisky. This isn’t hyperbole, this is one of the most exciting young distilleries within the entirety of the UK. The best thing is, having only so far released three years worth of their whisky, we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of what I believe they’re capable of.

“Just think about the conversation we’re going to have with consumers about this whisky in the future,” Max says. “Why is it different? What do you want to do in the whisky making process to give them the opportunity to make that connection?”

“We’ve not yet bottled any of our Derbyshire malt whisky, but when we do, we already know what the conversation’s going to be.”