The Vertigo of Bliss — Scotland’s Inseparable Relationship with Tennent’s Lager

It’s a Sunday, nearly midnight, and I’m in 8 Ball–a dilapidated yet bustling pool hall above the Scotia, an out-of-the-way folk bar in Glasgow city centre. Occasionally a buzzer sounds, signalling someone at the door—it’s the kind of place where the staff need to keep a handle on exactly who gets in, and when. The Dixie Chicks are on the jukebox for the third time tonight. Depending on how friendly the burly, silver-haired barman is feeling, there might be time to get one more round in, and maybe a couple more games of pool, if we’re quick.

I’m inside a small, cheap tent, in a damp field. A mobile phone sits half-submerged in the puddle that formed in the corner during the overnight rainfall. On the other side of the tent, a slab of cans sits next to a rucksack full of crumpled clothes. Music plays over a tinny speaker from a neighbouring tent, clearly audible through the flimsy material. The beer isn’t getting any colder, but it doesn’t matter.

A hundred wedding guests are packed onto a chequered dancefloor in the snug, darkened dining room of a Charles Rennie Mackintosh-designed country house. The open half-moon windows let in a welcome breeze as the guests thunder round the room, dancing the Gay Gordons to a live cover of The Prodigy’s Firestarter. The song ends and people flood the small bar, ready for shots and pints.

Photography by Matthew Curtis

These are a handful of my memories of drinking Tennent’s Lager. I have many more. It doesn’t matter what the occasion is; Tennent’s is a beer that features at every kind of gathering here in Scotland. One of several national drinks, Tennent's occupies such a key place in Scottish culture that perhaps only Irn-Bru is better known. It has a fan page on Facebook for its devotees, to whom it’s known as ‘Big Juicy.’ For many Scots it's the first beer we ever try, and it's been this way for a very long time.

***

Compared to the affluent West End and the heavily gentrified South Side, the East End of Glasgow is often overlooked as a cultural quadrant of Scotland's largest city. Yet it was once its beating heart.

Glasgow Cathedral was built here in the 1100s, and the burgh grew up around it. Nearly five centuries ago, when Glasgow’s population was a mere 4,500 people, the city's longest continuously-running commercial concern took its first steps. In 1556, on a site by the Molendinar Burn and less than a quarter of a mile from Glasgow Cathedral, Robert Tennent began brewing beer. In 1740, his descendants Hugh and Robert Tennent founded their own brewery on the same site. The Wellpark Brewery—named for the nearby Ladywell artesian spring—flourished, and by the mid-19th century became the biggest exporter of beer in the world.

The mid-1800s witnessed the beginning of the unstoppable global rise of pilsner-style beer, spreading quickly from Plzeň in Bohemia (now Czechia), across Europe, and on to the USA via German immigrants. Having spent time in Bavaria just a few years prior, Hugh Tennent (the great-great-grandson of Wellpark co-founder Hugh) was inspired by the appearance, flavour, and no doubt the success, of crisp, pale, cold-conditioned beer—and in 1885 he launched his own: Tennent's Lager.

From here, the success of the brewery went hand-in-hand with the growth of its flagship product. Over the next century, two new purpose-built breweries were constructed, still on the same site. Tennent’s were early adopters of new packaging technology, and in 1935 became one of the first breweries ever to can their lager.

In 1963, the same year they first kegged Tennent's Lager, J. & R. Tennent’s was acquired by London-based Charrington United Breweries Ltd. As the decades passed, the renamed Tennent Caledonian Breweries (TCB) was acquired several times over. In 2009, the Ireland-based C&C Group purchased TCB from AB Inbev in a deal worth £180 million, reportedly to reduce Anheuser Busch and Inbev’s post-merger debts. It owns the brand and brewery to this day.

Even the most successful of businesses aren’t immune to market forces, or human error, and in recent years, C&C have faced their share of issues: the mishandled implementation of a new Enterprise Resource Planning system in 2023, and a share value drop of around 20% following poor trading in early 2025. But it’s difficult to imagine anything ever permanently derailing TCB—just as it's nearly impossible to picture Glasgow without Tennent’s Lager.

***

When I left rural Morayshire aged 17 and moved to Glasgow to study at the University of Strathclyde, I made my new home at the edge of the East End. It was here I met my new friends, and became aware of a curious smell that permeated the air around this part of town. At the time, I might have uncharitably described it as being a bit like stale Weetabix.

The Strathclyde campus and its many halls of residence lie on the city centre side of Glasgow’s High Street. On the other side is Glasgow Cathedral, the Necropolis, and not too far beyond, Wellpark Brewery—the origin of that unfamiliar aroma. It took me months to discover we were less than half a mile from the source of the pints being served up for 50p on Friday afternoons at my student union. Not that this made any particular impression on me; I wasn’t drinking Tennent’s because of any interest in how it was made. I was satisfied enough just knowing where the smell was coming from.

These days, I'm much more familiar with its source; since 2013 I’ve worked in the beer industry. Four of these years were spent at Drygate Brewing Co—a small-batch production site set up in 2014 as a joint venture between Williams Brothers of Alloa (33 miles northeast of Glasgow,) and Tennent Caledonian Brewers. Drygate occupies a building on the Wellpark site, just outside the perimeter fence of the main yard. The walk there from Glasgow Central Station would always bring back memories of my first year at uni; working there felt like I had come full circle.

““Selling over a million hectolitres a year says to me that a lot of people enjoy drinking it, and to them it must be the best lager in Scotland.””

The smell of malt being mashed in at Wellpark is no different to that of any other brewery I've spent time in. The underlying process of making beer is always essentially the same. But Wellpark itself is unique. The sprawling site has the distinctive feel of a campus that has been extended and added to over the years, rather than being custom-built in a single swoop. The entrance and visitor centre is bright and inviting, if a little slick and corporate. The offices are like any other large open-plan workspaces; clean, minimal and very JLB Credit. Wander through and you'll be greeted by cheery waves; the team at Tennent’s are a friendly and engaged bunch. But why wouldn't you be, working for a bona fide Glaswegian institution?

Head a little further into production, packaging or distribution and you'd best have a guide handy. Brewing equipment fills every available inch of the asymmetric buildings, in such a way that it's impossible to tell whether the kit was squeezed in or the bricks were laid around it.

The mash filter, an enormous piece of equipment used to improve wort extraction in larger breweries, is particularly impressive. The top half is visible on one floor, with the remainder sealed off yet accessible from the level below, as if the whole thing was so heavy that one day it just sank through the floor. In the packaging hall, catwalks hanging high above the canning line require careful navigation, with low pipes and multiple levels to manoeuvre through. The production of Tennent’s Lager takes place over so many different buildings, that to follow it, you need to cross multiple roads. The campus is too well-maintained to describe it as ramshackle; it has wonderful character. The kit has clearly evolved many times over the years.

“The main changes at Wellpark [are the] new brewing and packaging plant and equipment,” says Keith Lugton, Wellpark's recently-retired master brewer of 47 years.

“Also, [an] investment in environmental projects to reduce the carbon footprint and support sustainability,” Keith tells me. “You need to modernise and move with the times, but it was always changes to the physical space rather than the spirit of the brewery.”

Despite the size of the business, the ever-changing demands of consumers, and the challenging market conditions facing the beer industry (which not even Tennent’s are impervious to,) the team at Wellpark, like the overwhelming majority of breweries, continue to care deeply about producing and selling quality beer. Although they don't focus heavily on it in their marketing campaigns, this starts at the most basic level—the ingredients.

“The best ingredients are the building blocks for a great beer,” Keith says. “Malt, barley, wheat, hops, [and] water are all key ingredients in the Tennent’s recipe. The yeast used is also key to providing all the other complex flavour characteristics produced during the fermentation process. It’s the proportions of each [ingredient] which marry together to produce the flavour profile we look for in Tennent’s Lager.”

Tennent’s Lager is brewed with soft Scottish water from Loch Katrine, around 30 miles north of Glasgow, supplied to the city via an impressive series of aqueducts. The grist incorporates both malted barley and wheat, the latter providing a high protein content, responsible for the lager's distinctively long-lasting foamy white head. German-grown Herkules hops are deployed with exacting efficiency to deliver the correct level of bitterness to balance the flavour profile.

It's a fine line to walk. This is a beer with a 140 year history, not to mention Scotland's most popular lager. You don't get to be that successful by challenging the tastebuds of the nation. It has to taste the same every time, and it can’t be overly assertive or people will drink less. Its simplicity is its strength. And yet arguably, it’s this lack of intensity that has led many to criticise Tennent’s Lager as an inferior product.

“They're obviously misguided individuals,” Keith remarks with his trademark good humour.

“Tennent’s Lager would not be what it is today, and has been over the decades—Scotland’s number one beer—[if it were a poor quality product.] Selling over a million hectolitres a year says to me that a lot of people enjoy drinking it, and to them it must be the best lager in Scotland. To maintain brand loyalty, product quality is key.”

And maintain loyalty, it does. Like most other successful brands, the quality is there—even if some people disagree. Quality alone, though, is rarely enough to assure long-term success. Quality doesn't lead people to pick the cans off the shelf in the first place. It's one of the biggest challenges facing new businesses. But Tennent’s is not a new business.

With Tennent’s, it’s not so much a question of ‘how did they get to the number one spot?’ as ‘how do they stay there?’ Several factors ensure Tennent’s remains Scotland’s favourite lager. For starters, the company has its own distribution arm and a large sales team covering the entire UK, courtesy of C&C's various subsidiaries. Secondly, thanks to economies of scale, it’s produced, sold into trade and retailed at a very accessible price point. And perhaps most crucially, Tennent’s has a brand identity as consistent as the lager itself.

***

“There's an omnipresence to Tennent’s,” says David Freer, managing director of O Street, a Glasgow-based design agency.

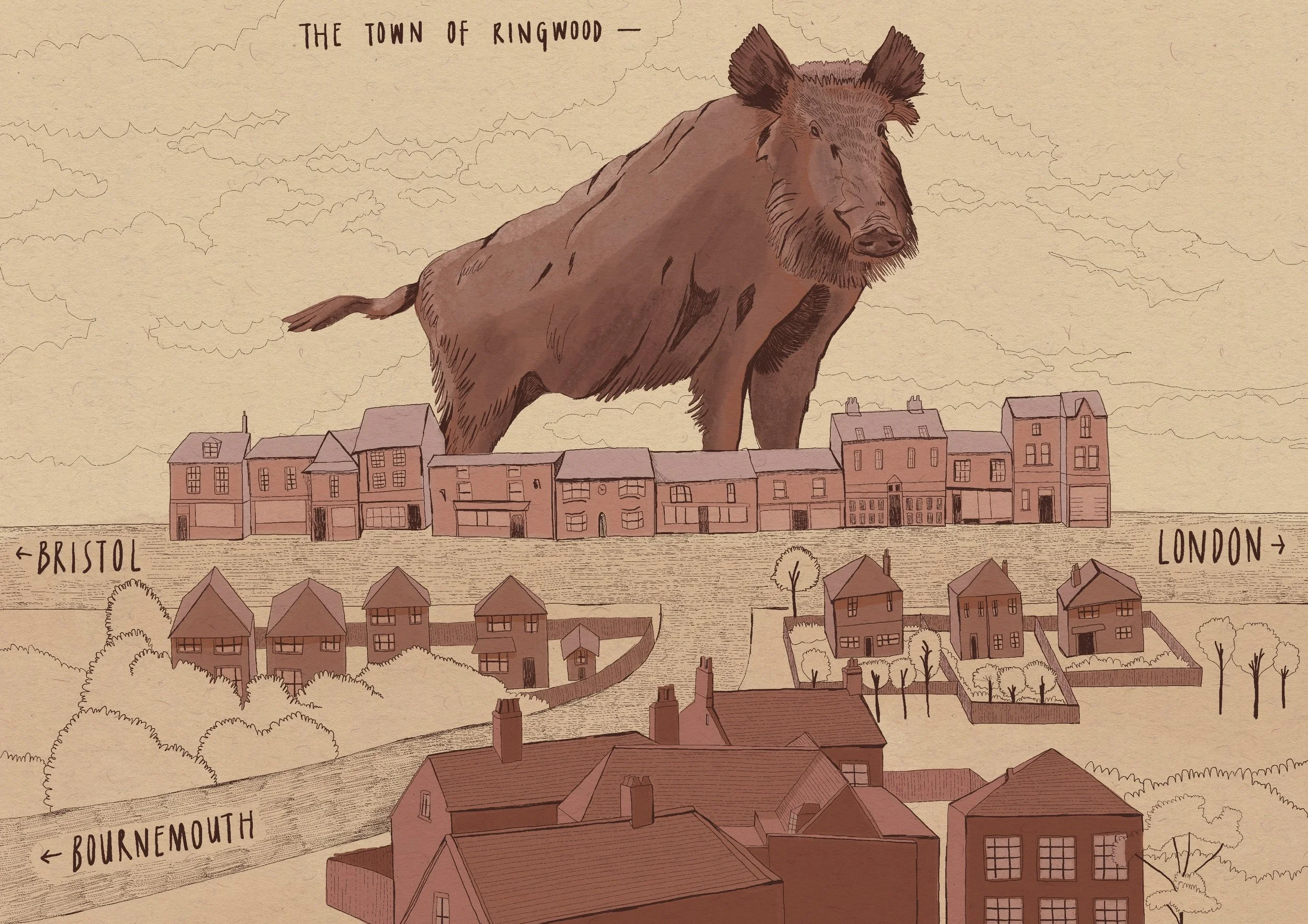

“People like it because it's an institution; Tennent’s is always there,” David tells me. “I remember—and we've all done this in Scotland—driving into a weird town or village you’ve not been before, not knowing where to go, and seeing the glowing red T.”

These illuminated signs can be found from the farthest reaches of the Highlands and Islands, all the way down to the borders, poking out above the door of hundreds of pubs along the way. They provide a comforting reassurance that even in an unfamiliar drinking spot, you're going to know at least one thing on the menu.

““That bridge of being an old, established brand, but actually looking modern, is probably quite a strong asset that you can’t just copy.””

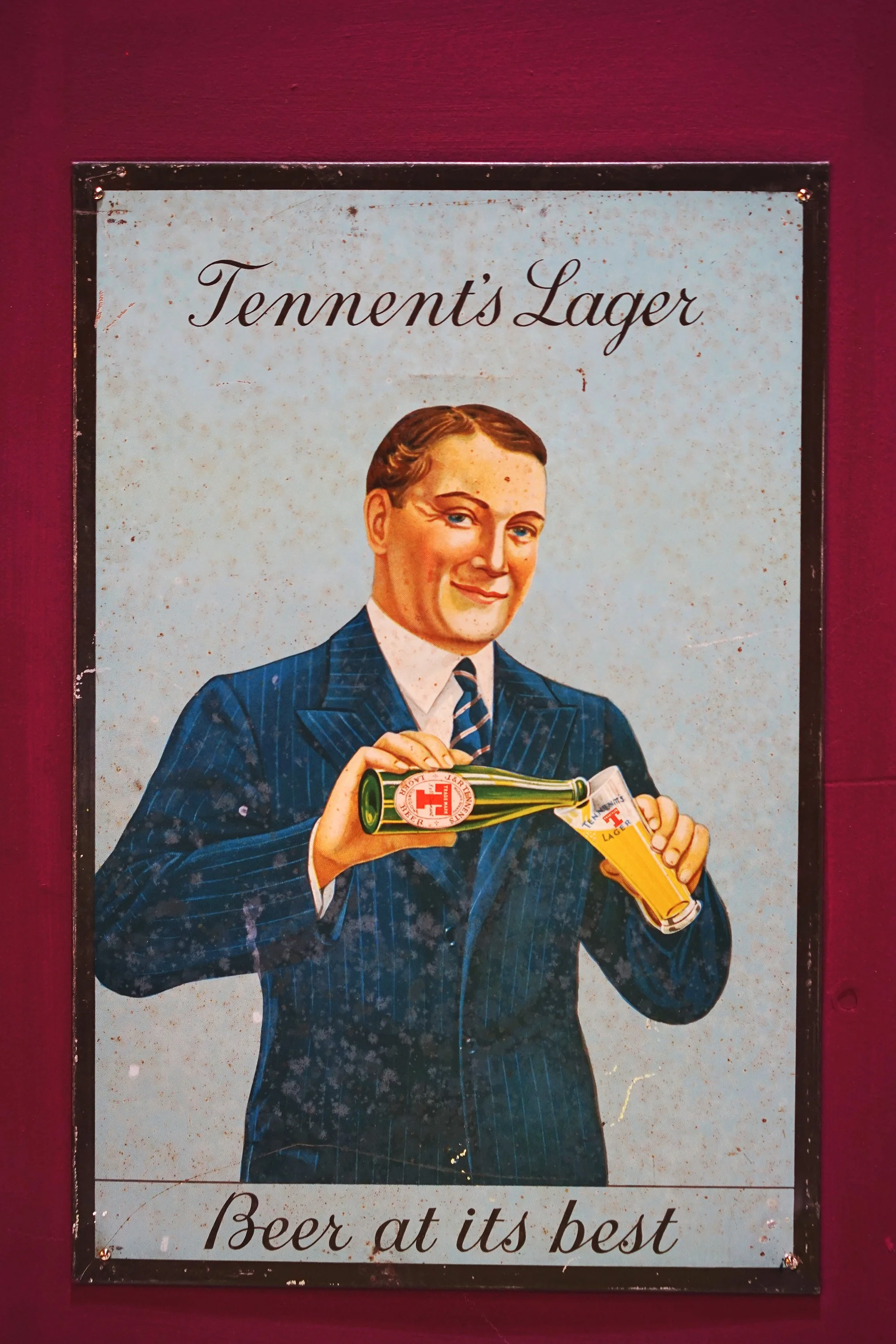

Although Bass famously established the first UK trademark in January 1876 when the Trademarks Registration Act came into effect, Tennent’s were only a couple of months behind. Their inimitable red T was registered in March the same year. Perhaps surprisingly, it hasn't changed a bit in all that time. You might expect a logo that's hundreds of years old to look dated—yet somehow the bold, heavyweight character with its distinctive sharp-cornered block serifs still looks at home on cans, fonts, beer mats and merch.

“I think there's a weird thing about it, that on the one hand it's got history and heritage, it's nostalgic, but visually it's quite modern looking,” David tells me.

“That red and yellow, it’s like McDonald's. That bridge of being an old, established brand, but actually looking modern, is probably quite a strong asset that you can't just copy.”

For young breweries, the temptation to revise and rebrand, to tinker and update, is strong. Speaking hypothetically, were David to win the Tennent’s account and be asked to give the design an overhaul, he admits he’d be a little worried. Why would any brand worth its salt throw something so distinctive away?

“A brand of course is more than just a visual asset,” David says. “It's how they manage their profile publicly… and I don't think we should underestimate the fact that subliminally, or consciously, you see a lot [of Tennent’s branding] around.”

It's not just the lager and the logo that are consistent. In Scotland, Tennent’s is everywhere. The brand extends far beyond the confines of pubs and restaurants, and into sports venues, music festivals and public transport; past supermarkets and kitchen fridges, into living rooms and onto TVs.

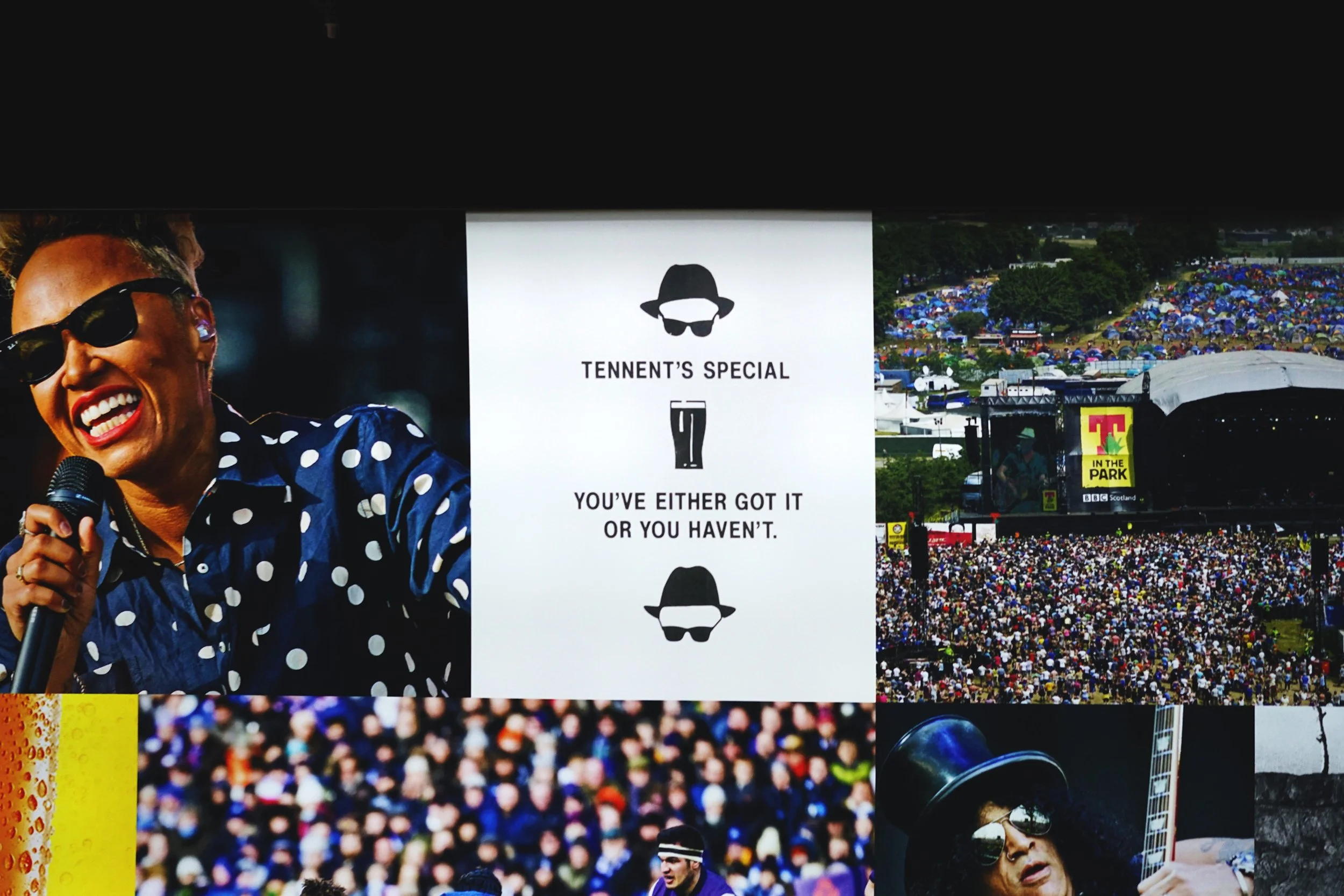

Although the margins made on the sale of Tennent’s Lager are low, the sheer volume produced returns enough profit to fund above-the-line marketing on the world stage. Tennent’s sponsors both Scottish Football and Scottish Rugby's men’s and women’s National Teams, plus Edinburgh Rugby and Glasgow Warriors. It’s highly visible to a broad cross-section of the Scottish population, and that's before we factor in their own long-running music festival and decades of memorable (and, admittedly, sometimes cringeworthy) advertising campaigns.

It says a lot, good or bad, that many of the TV ads I recall from growing up in the 90s were for Tennent’s. Guinness might be remembered for its timeless ‘tick followed tock,’ but 20 years later I'm still saying “take a drink big man” in stilted English. And I can't hear Daddy Cool without thinking of a man dancing with a fridge.

Many of their ads subverted Scottish tropes; Pintlings was voiced by the cast of Glasgow-based police procedural Taggart (“murder one tonight”) while Thailand played on Scottish stereotypes through the lens of the fictional McAndrews bar. In a rare display of earnestness, one ad featured a homesick young businessman leaving London behind him and heading back to Edinburgh, set to Frankie Miller’s emotional rendition of Caledonia.

Some ads didn't lean into Tennent’s Scottish roots at all. Japan featured a group of twenty-something friends searching for an exotic imported lager, while in Bollywood, the brewery was portrayed as the property of an Indian mogul in a fictional movie. The focus was on people and humour, rather than ingredients or heritage—a thread that runs from the 1970s, when Tennent’s featured Morecambe and Wise in a TV ad, right through to their current campaigns.

The Scottish Men’s National football team is notorious for failing to reach the group stages of international football tournaments. So when the side qualified for EURO 2024, Tennent’s took full advantage of their sponsorship with a full through-the-line campaign: TV ads, billboards, social media, events and more.

“I really enjoyed what we did around the Euros last year,” Max Fraser, Tennent’s Brand Manager, tells me. “We celebrated 50 years as original supporters of the Scotland national team—so it was a seminal moment in the history of the relationship.”

Perhaps it’s Tennent’s refusal to fixate on ingredients and history, and lean into the things that bring us all together, that keeps them at the top spot in Scottish beer.

“The Tennent’s brand has a personality of wit and humour, which for consumers makes us a brand of the people, one of them,” Max adds.

Of course, to truly be a brand of the people, you need to be a brand of all the people. Ideally, this doesn't involve a campaign that objectifies 50% of them.

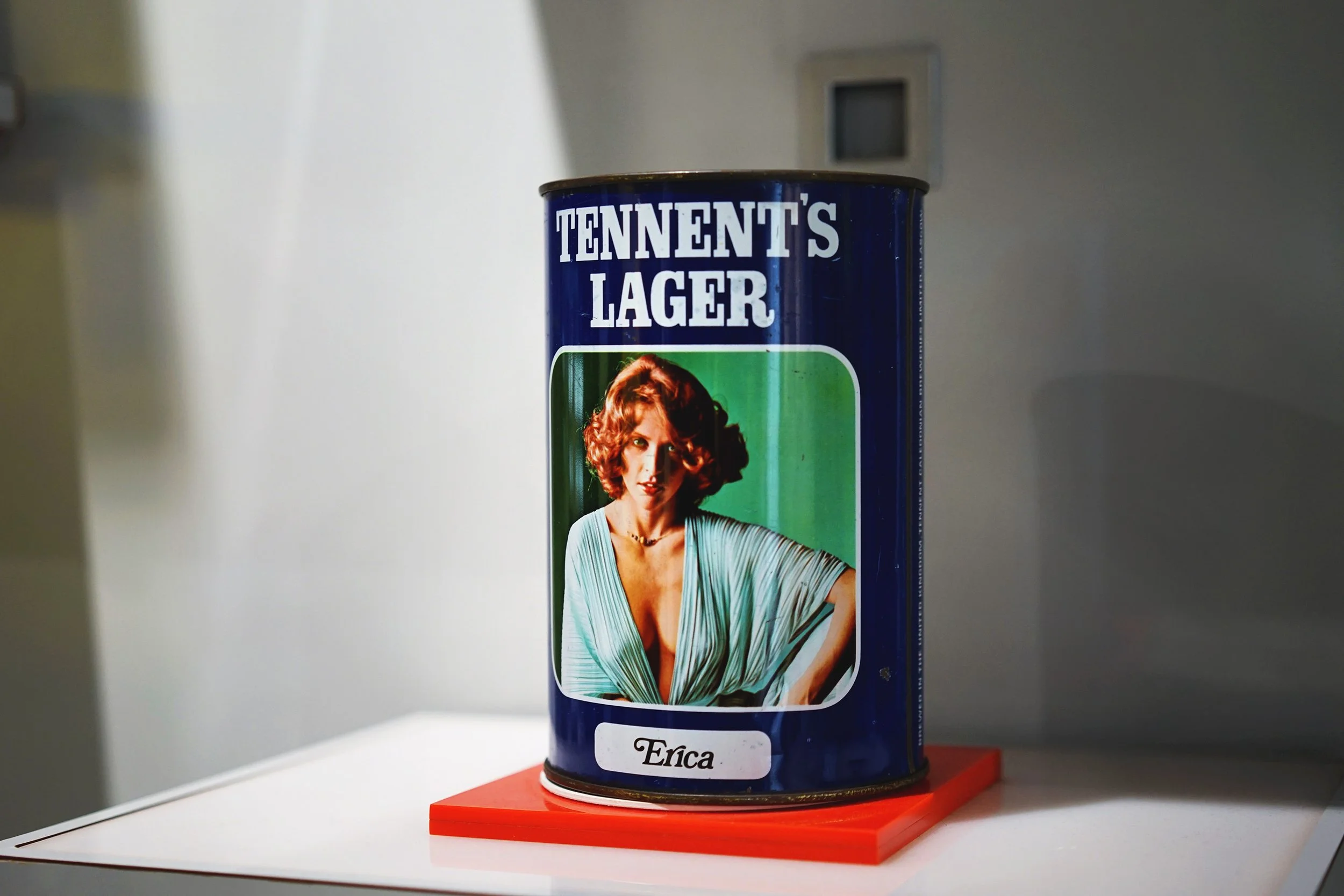

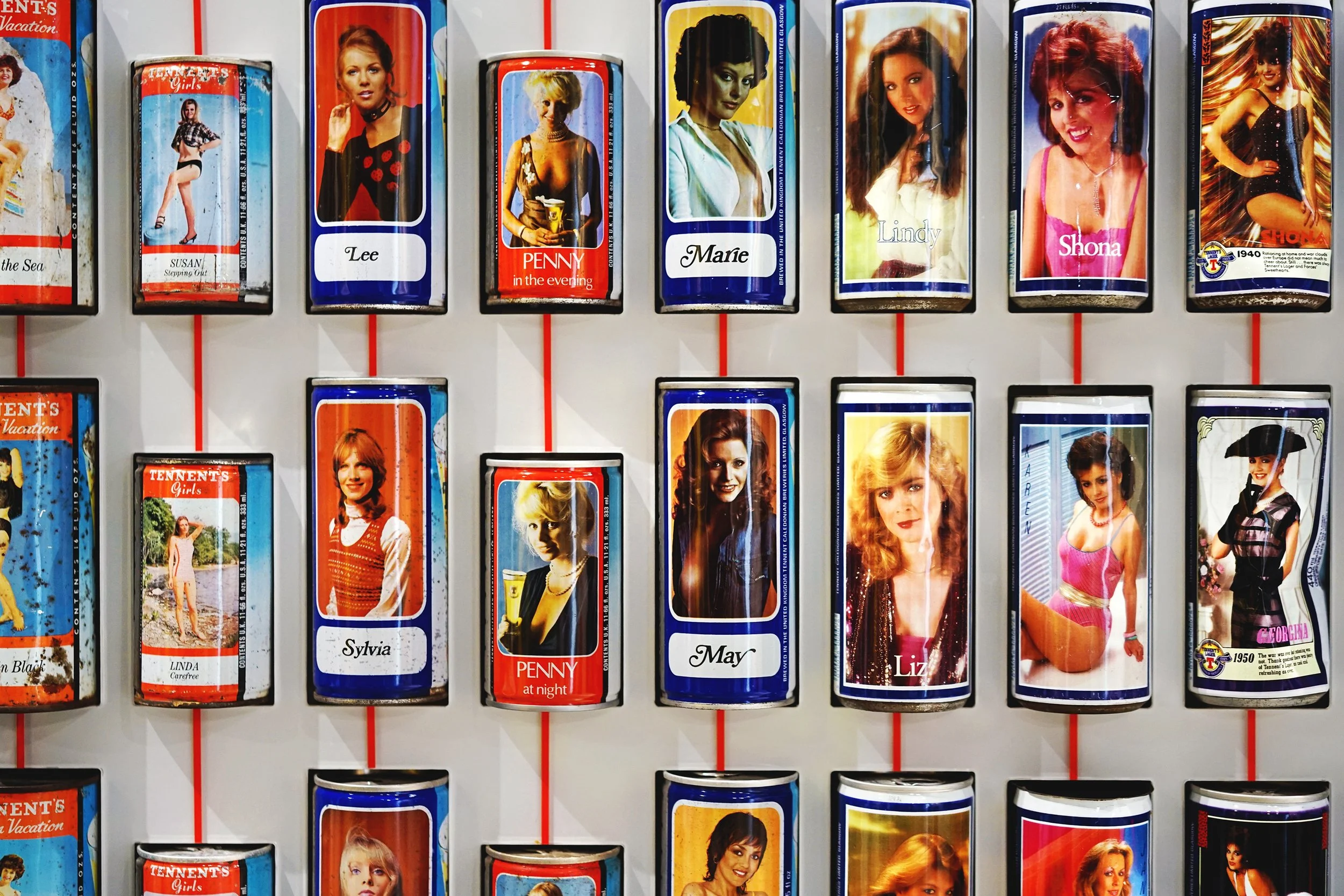

In the sixties Tennent’s launched arguably their most infamous ad campaign—one which ran for almost three decades. For three years prior, the lager had been packaged in cans depicting famous UK landscapes and buildings, which were popular with British soldiers posted abroad. Then, in 1962, they released a can featuring the Trafalgar Square fountain—but on this edition, there was a young woman (Ann Johansen) standing by the water feature. Upon receiving numerous letters from troops asking to see her on more cans, Tennent’s seized the chance to increase sales, and Ann appeared on several follow-ups.

From 1965, Ann was joined by other young women, each featuring on one or more cans (along with taking part in brand activities and attending sporting events,) and the Tennent's Lager Lovelies were born.

“My introduction to Tennent’s Lager was back in the 1960s when I was about six or seven,” says Hilary Jones, Scotland Food & Drink's chair of the Brewing Industry Leadership Group. “I don’t remember cans of Tennant’s without the Lager Lovelies, [they were] just pretty ladies on the tins to me.”

The cans featured photography of a series of women, increasingly scantily clad as the years went on. Tennent’s—like many others at the time—came to understand just how successfully sex sells.

“Naked pin-ups were the norm in male-only environments, [and the Lager Lovelies] were just an extension of that ‘normality’ and not seen as misogynistic [at the time],” Hilary tells me.

““I don’t remember cans of Tennant’s without the Lager Lovelies, [they were] just pretty ladies on the tins to me.””

Hilary, having joined the industry in 1981 as Scottish & Newcastle’s resident yeast custodian in Edinburgh, recalls a rivalry between Tennent’s and her own employer.

“Tennent’s was considered a Glasgow beer, for old men and football supporters, a leading ‘lager lout’ brand. McEwan’s branding was classier than Tennent’s, through female eyes–perhaps the presence of the Lager Lovelies reinforced our view that Tennent’s was not something any self-respecting woman would buy.”

In the 1990s, a survey revealed that while the majority of male participants polled were now ambivalent towards the Lager Lovelies campaign, 15% believed the women should appear topless. Not long after this, Tennent’s finally pulled the plug on the campaign.

The women involved reportedly found the experience rewarding, but the concept itself was not a positive one. “It was perceived as downmarket. Lager Lovelies [...] just seemed tacky and a bit juvenile,” Hilary tells me. Were that campaign to be run under today’s standards, she has no doubt it would be perceived differently.

“I would reject any brand whose words and pictures offended me in any way; blatant sexism, rudeness, racism or political extremism,” she adds.

After the campaign ended in the nineties, Tennent’s had something of a brand revival. In 1997 they began working with the Leith Agency to increase their appeal to younger audiences, resulting in the Chauvinist and Feminist ads (which now feel a little, “look mum, we're self-aware.”) But, crucially, this was also the decade that they first sponsored what went on to become a jewel in the crown of the Tennent’s brand.

***

T in the Park was a music festival that ran from 1994 until 2016. Festival co-founder Stuart Clumpas wanted it to be Scotland’s flagship music event, and despite humble beginnings Stuart and his colleagues achieved their goal. A weekend of live music—featuring a little-known group from Manchester called Oasis billed halfway down on the King Tut's stage, and headlined by Blur and Primal Scream—was enough to bring 17,000 people to Strathclyde Country Park for the inaugural event in 1994. Despite making a reported £1 million loss, this was considered enough of a success to bring it back again, and just three years later, following a move to Balado in Kinross, the festival was attended by 70,000 people.

As the years passed, T in the Park became Scotland's answer to Glastonbury. World-famous acts headlined, hundreds of thousands of guests camped out, and countless pints of Tennent’s Lager were served up to the masses. Slabs of cans, for taking back to your tent to continue the party long into the night, were available too. And party we did. T in the Park, like its namesake lager, attracted a wide cross-section of the population. It was for everyone.

In the end, a combination of factors saw the death of T in the Park. The Balado airfields upon which it was pitched lay over a petrochemical pipeline running from Aberdeen to Grangemouth. Despite protestations, the health and safety executive insisted the event could no longer take place at its spiritual home. This forced a 20 mile move to the Strathallan Castle estate, and from there the event was plagued with issues, including working around a protected osprey nest, some particularly egregious Scottish weather, and worst of all, the deaths of two teenagers and a serious sexual assault.

There was no going back—even if a better site could have been found, the brand was now forever linked to tragedy. T in the Park was gone, for good.

One thing is certain: no matter how big a brand, event, or advertising campaign, it will in time come to an end. Fashions pass, fleetingly or not. Audiences change. T in the Park ran for 23 years. The Lager Lovelies lasted for an astonishing 29—long enough for two consecutive generations to grow up seeing them on cans. But for now the Tennent’s brand, and the beer itself, live on. The former evolves, the latter does not. Both are crucial to the success of a modern, timeless product. But which is more crucial—beer, or brand?

“The two go hand in hand,” Keith says. “Product quality is critical to a brand’s success, especially in the drinks industry. So it would have to be product quality over brand identity. However, [losing one] would be like losing a twin."

Max Fraser agrees: “As a marketeer, I’d love to go for the brand, but I do feel the longevity of Tennent’s is built on the product quality. [...] You can build excitement through [a] brand, but ultimately consumers want a quality product and if you can’t deliver on that you are destined to fail.”

***

I'm sitting with a pint of Tennent’s in the beer garden at Drygate Brewing Co. Drygate, once the name of the Tennent’s brewery, is now also a taproom and restaurant, and is the only place that sells unpasteurised Tennent’s Lager from a keg. (T in the Park once also held this honour.)

The only way you'll taste a more accurate version of what the brew team aims for is by sampling it directly from the enormous conditioning tanks at Wellpark, or perhaps on one of their taste panels, run by Brian Black, who has worked in their quality control team for 24 years. Outside of Brian's sensory suite, this is not the kind of beer that is typically pored over.

Tennent’s branded glasses are tall and straight-sided—they’re designed to deliver pints of beer quickly and efficiently down the drinker’s neck. They don’t trap delicate aromas—so picking apart the flavour profile of my Tennent’s is going to put the sensory analysis skills I developed while training to be a Master Cicerone to the test. I’m suddenly aware that it’s never occurred to me to do this before.

On the nose there's a big waft of bread; some raw dough, some baked crust. Beneath it, the lightest, faintest touch of the smoky phenols you’ll find in a Belgian pale ale. There's a hint of sulphur too; it provides a freshness to the aroma.

Tasting reveals a subtle fruitiness, but mostly toasty character from the pale barley malt. There’s a fullness to the body, almost an oiliness, from the wheat. Sweetness piles in up front, but as I go back for another pull, a grassy, almost herbal bitterness creeps in. It’s not resinous, like an IPA, but it’s more biting than most mass-produced lagers widely available in the UK that I can think of.

Of course, I'm enjoying the unpasteurised version, served on tap just a couple of hundred yards from the source. Most Tennent’s delivered around the UK is subject to a short blast of heat after packaging, killing off any spoilage bacteria, thus rendering the beer stable for much longer. This process can be deadly to the delicate hop aromas of certain types of beer. For simple lagers however, pasteurisation doesn't have the same effect. It speeds up the ageing process by which all beer is affected, and dulls the flavour a little, but the end result remains close to its pre-treated form.

As far as the pantheon of beer goes Tennent’s ranks low on the flavour intensity scale. But within the realm of lager, it holds its own. This is a beer that beat Camden Town Brewery to the concept of ‘somewhere between helles and pilsner’ by about 120 years. Treated right, and not plucked from a slab stored in a warm garage, it absolutely does the job. Keith was right—you can turn your nose up if you want, but you’d be misguided.

Finishing my pint, I decide that one wasn’t quite enough, so I'm having a second with a friend who has just joined me. The aromas and flavours of the beer in front of me are already forgotten. The closest I get to engaging with my pint is compulsively turning the glass so the iconic red T faces me after every sip.

Tennent’s Lager turned 140 years old in 2025. In the last 23 of those years, it has come to represent several things to me. As a student, it was my go-to cheap beer. I couldn’t even guess at how many pints I poured during my seven years in hospitality. It was taboo during my time working for another Scottish brewery, BrewDog, and as such became a guilty pleasure among the team (and no doubt among many others in the industry.)

Since then, I have witnessed a gradual rebalancing of the role mass-production occupies alongside the artisanal. Pabst Blue Ribbon became cool. Guinness became cooler. More people are choosing to drink British regional beer brands like Landlord or Bass for their simplicity, their consistency and their timelessness. And in Scotland, Tennent's Lager was, and is, that beer.