Sound as a Barrel — In Conversation with Gareth Young of Glasgow’s Epochal Barrel Fermented Ales

Tucked away on an industrial estate just north of Glasgow city centre lies one of Scotland’s—if not the UK’s—most exciting young breweries.

Wedged between the M8 and the Forth and Clyde Canal, Epochal Barrel Fermented Ales sits in an area of great industrial pedigree. Just across the water was once Scotland’s largest distillery, Port Dundas, which produced 39 million litres of grain spirit per year in its heyday. The ruins of a site formerly operated by Bairds’ Maltings lie just around the corner.

Photography by Jonathan Hamilton

Alongside the brewery runs Pinkston Basin, the water of which was warmed from the overflow of Pinkston Power Station—built to generate electricity for the Glasgow Corporation Tramways network. Today, the basin is a watersports centre, where water skiers and wakeboarders whoosh past on a zipline as Epochal’s owner and founder Gareth Young welcomes me into his one-man brewery.

The approach here is one of exactitude and speaks to Gareth’s brewing philosophy and academic underpinnings. The beers are individual and represent Glasgow’s past, present and future. Epochal’s reinterpretation of traditional styles reflects the city’s industrial and brewing heritage. At the same time, the brewery itself forms part of the regeneration of the canal, helping to breathe new life into this post-industrial landscape.

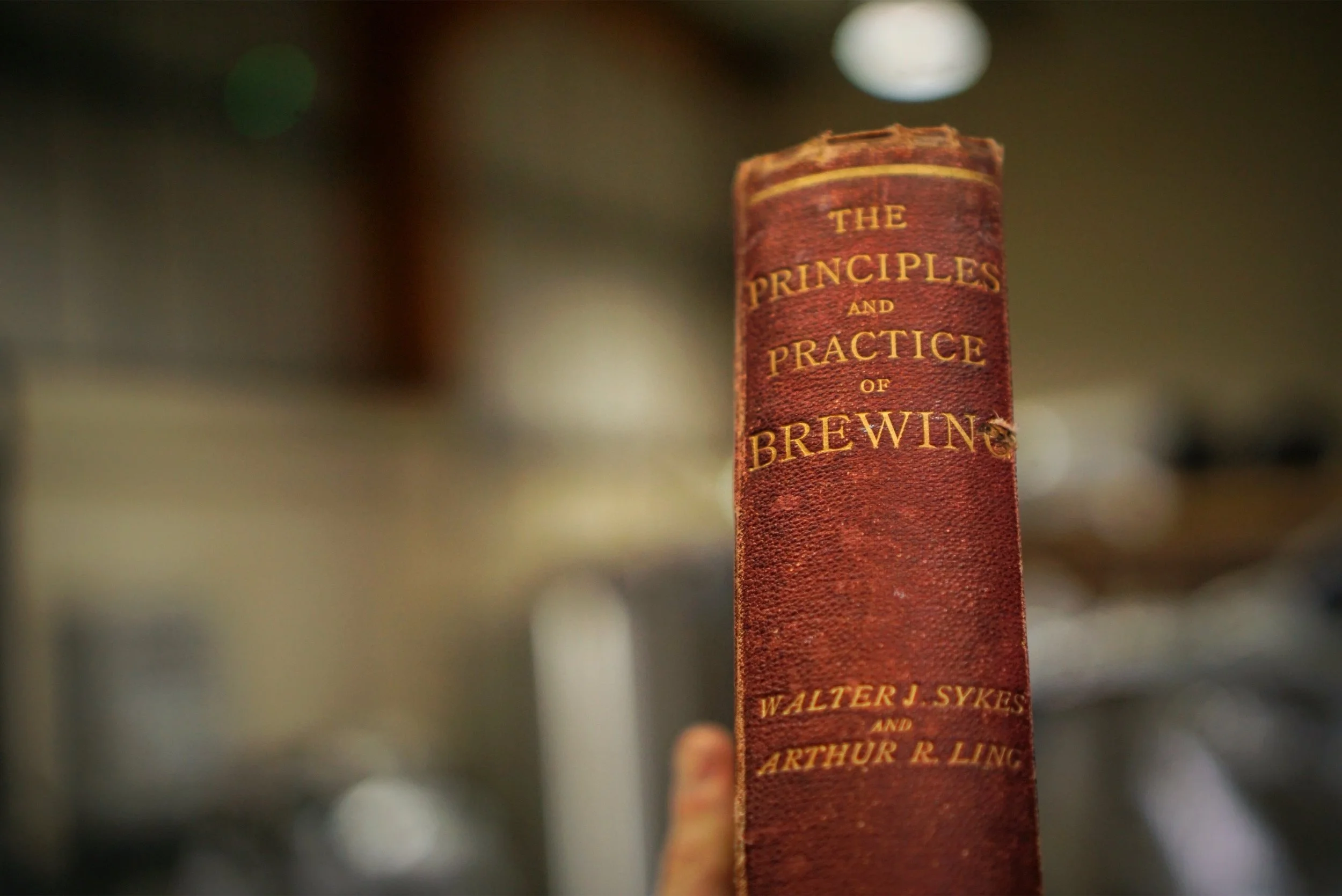

Making use of whisky and wine barrels to create barrel-fermented stock beers that draw on centuries of tradition—Gareth takes inspiration from the rich history of funky pale ales, porters, stouts and Scotch ales (also known as wee heavies) that Scotland was famous for in the 19th century, during Scotland’s golden age of brewing.

““The approach here is one of exactitude, and speaks to Gareth’s brewing philosophy and academic underpinnings.””

Gareth uses the old term ‘stock beer’ to capture the combination of complex microbes and wood-ageing he employs. While stock beers were historically those laid down to age in an era before the role of yeast in fermentation was fully understood, ‘running’ or ‘small’ beer referred to those made with secondary mashes to create a lighter beer for quick consumption.

Terms like locality and sense of place are important considerations, informing the choice of barley (always Scottish, mainly sourced from Crafty Maltsters in Fife), as well as the unique house microflora and historic brewing recipes employed.

Fermenting with house Saccharomyces cultures in open fermenters, followed by a long, slow fermentation in oak with Brettanomyces strains and whole cone hops, the resulting beers are delicious and uncompromising—harking back to Scottish brewing traditions once at risk of being lost, but slowly gaining ground again today. His charmingly cobbled-together set-up, including grundy tanks and Burton-inspired cleanser, reflects an approach that makes use of old and new techniques and technology alike.

Epochal specialises in barrel-aged pale ales, table beers, Scotch ales, porters and stouts—the latter two having a rich history in Glasgow.

The beers undergo an extended dry hop for the duration of their secondary ageing. The mature beer is then bottle-conditioned with a small portion of one-day-old fresh beer, a process employed by one of Scotland's top 19th-century brewers, the Glasgow-born James Steel. The entire process takes anywhere from three months to a year, resulting in beers you can ponder over, or drink for pure pleasure, depending on your mood.

The Fixed Stars is a clean and malty light porter based on a James Steel recipe, while Green Label uses Maris Otter barley and brings layers of Bretty funk. Gavagai, meanwhile, is a blend of pale ales in a third-use rye whisky cask, using Scotch Common malt and a blend of English and German hops to serve up pineapple and coconut notes on the nose—contrasted on the palate with a refreshingly light and sharp finish aided by dry hopping with Nelson Sauvin.

Few of his beers are quite as sessionable as the earthy Scottish stock ale The Prince of Cloud and Sky; a blend of two pale ales again, this time with noble hop Hallertau Mittelfrüh. It is crushable yet complex, floral, fruity, and beautifully bitter on the finish.

Gareth’s background in abstract academic philosophy is apparent in Epochal’s house style: from the esoteric names of the beers to the approach of updating old traditions, and the bewildering knowledge of brewing heritage that complements the modern techniques at the brewery. Each beer is unique, complex and carefully crafted—rooted in the past yet firmly in the present.

I sat down for a chat with Gareth at the brewery to find out what motivates Epochal’s eclectic approach to beer-making.

***

Robbie Armstrong: How did you end up going from a background in abstract academic philosophy to brewing beer? And what did the former teach you about the latter?

Gareth Young: My interest in beer and my interest in philosophy ran parallel for a long time. I got interested in both of them at about the same point, around the time I started university in 2003. I've always been quite an obsessive person and I got obsessed with both of them. I was passionately learning what I could about them and felt like I wanted one of them to be a job and one of them to be serious.

Initially it seemed like the way to do that was to pursue a job as a philosopher lecturing at uni and have homebrewing as a kind of a hobby—a serious hobby, but a hobby. And then I got a little bit disillusioned with academia—lots of stuff like applying for grants and publishing, things I was never very interested in or particularly good at. I loved the philosophy, I loved the research and the teaching, but those other aspects of it just weren't for me.

So around the same time that I started to feel that, the ideas for Epochal were coming together. I was becoming interested in sense of place and interested in Scottish brewing. And I won a big home brew competition in 2015. I was the UK national home brewing champion, which came with a £5,000 cash prize.

That was probably when I felt a bit of impetus to actually do it. I got my PhD and won that prize in the same week. It was pretty wild.

RA: As an award-winning home brewer who’s made the leap, what advice do you have for other homebrewers looking to turn pro?

GY: Don't do it!

If someone wanted to go professional, my number one piece of advice would be to get a job in a brewery and work professionally at it for a while. If someone wanted to level up their homebrewing, I would say that fermentation is the most important bit of brewing.

““A lot of what I do comes from thinking philosophically about the notion of sense of place.””

If you get an idiot and an expert, and you make one beer where the idiot does the brewing side of things and the expert manages fermentation, and then they swap—the one where the expert is in charge of fermentation will always be the better beer because that's where beer is made or broken.

RA: You’re a firm believer in fermenting your beers slowly over long periods in barrel—tell us why and what benefits this brings to the finished product?

GY: The thing that it brings to the beer is complexity, the kind of interactions that happen in barrels between oxygen and the compounds and the wood, and the fact that the batch is split between so many barrels, each of which is different, which can then be blended. It just yields the kind of complexity that you can't achieve any other way.

RA: What should we call your style: ‘stock ale’, ‘mixed fermentation’ or something else?

GY: Mixed fermentation is an extremely broad term, especially now. Some of the beers that are called mixed fermentation are about as far as it's possible to get from what I do.

I feel like we need something specific that picks out what I do in a useful way. And the last time that was a big deal, there was a word for it, which was stock beer. Stock beer is aged in wood with Brett, running beer isn't aged in wood, or with Brett.

RA: How do locality and site-specific characteristics affect the way you brew?

GY: A lot of what I do comes from thinking philosophically about the notion of sense of place.

And that's what the big inspiration is, trying to make beer that in a meaningful sense is Scottish. I use local barley, that's one way of connecting to place. The local water supply is distinctive, Loch Katrine's water is extremely soft. It's like Plzeň’s water, really.

The climate has a big impact. Nothing here is temperature controlled[…] which means that the change of seasons has a huge impact. Basically, the beer is lagered for a significant portion of the year because it's so cold.

That kind of dreich oceanic climate to me has a very, very significant impact on the way fermentation progresses in wood.

House microbe cultures, that's a kind of sense of place, that's a connection to here, as is the engagement with Scottish brewing traditions, drawing inspiration from the traditions and the people involved in making Scottish beer—whether that's Edinburgh pale ale brewing or Glasgow porter brewing.

RA: History is clearly important to you, from historic styles and old recipes to methods that draw on centuries of beer making tradition—does learning from the past help you look forward?

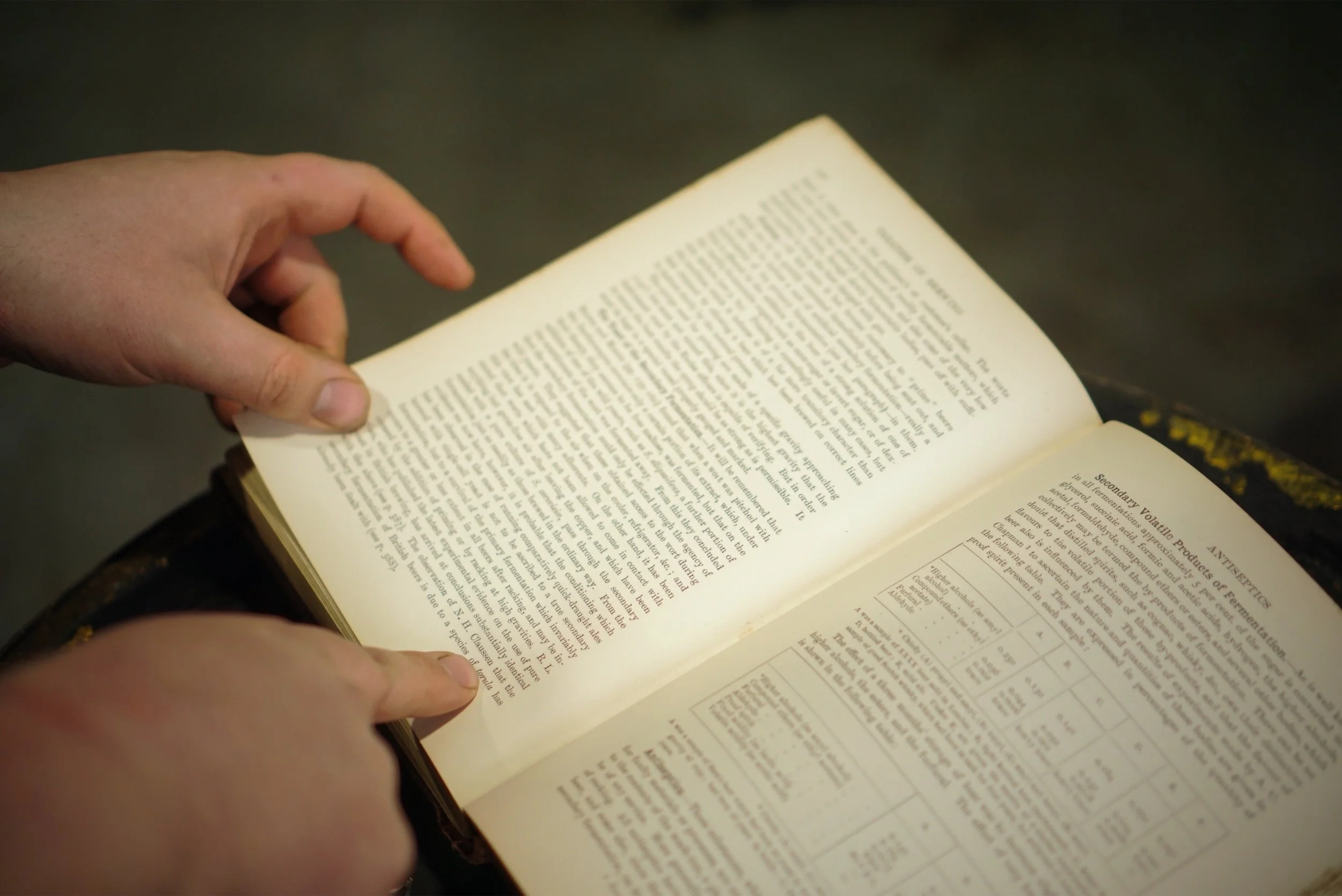

I'm really interested in modern brewing science. I read all the books about modern hopping that people use to make New England IPAs. I'm interested in modern craft brewing. I take interesting ideas where I can find them and it turns out there are loads of them in old brewing, they knew what they were doing back then.

Finding out about Scottish brewing and, and more broadly, I suppose, UK brewing in the 1800s—it's one of the big golden eras[...] The UK, especially Scotland, was an export market for beer. Basically that came from Brettanomyces. Exporting was difficult for most drinks because of their tendency to go flat, oxidise or otherwise deteriorate. You could export whisky and other spirits, fortified wines and some high end wines like Claret, but a lot of wine and beer would tend to go off. The way old UK brewers learned to harness Brettanomyces allowed them to overcome these difficulties.

Brettanomyces means British yeast and it was identified as being a crucial part of these beer styles, like pale ale and porter that were exported at the time. Because all the beers are packed in wooden casks, if they're not continually fermenting in the cask, they just go flat—obvious when you think about it, because wood is porous.

Brett continually ferments in the wood, keeps the beer charged with loads of CO2 and produces extra flavour. This gave British beer the ability to last, as well as the fact that technologically brewing was very advanced, especially in Scotland. A lot of inventions now that people take for granted were invented by Scottish brewers at this time.

RA: What have you learned about Scotland’s place in the world of brewing from this research?

GY: Scotland was one of the top brewing countries in the world. Partly it's because we have a small population over a large area. So if you want to make a serious business, you have to export. It was a big deal—the Scottish brewing industry was much bigger than the whisky industry in the 1800s.

For most of the 1800s, Scotland exported more beer than the French did wine. Whisky only really became something that was capable of being high-end and desirable in the export markets maybe in the 1800s. The big names in Scottish brewing were the big names in world brewing. Scottish beer meant something. You find these adverts in newspapers in the Netherlands for not just Scottish beer, but Alloa table beer, Edinburgh ale or Glasgow stout.

People had a regional understanding of Scottish brewing in the 1800s, so it was huge. Scottish breweries got hit harder by the collapse of the export trade, the collapse of the British empire. All the export was happening through the veins and arteries of the empire. Good for the world, bad for Scottish beer.

““I take interesting ideas where I can find them and it turns out there are loads of them in old brewing.””

In some ways, I feel like, in Scotland, we don't really feel like we've got beer in our bones. People think that whisky is our thing, but if you hop over the border to Yorkshire people feel like good beer is their thing.

I think we've lost that a little bit. And seeing how big a deal it was in Scotland in the 1800s, it makes you appreciate that there is a big tradition of doing all this stuff here.

RA: Tell us about the 126-year-old bottle of McEwan’s you managed to get your hands on from a diver on the wreck of the Wallachia, which sank off the Scottish coast in 1895.

GY: While it tasted old and weird, the lack of oxidation meant there were aspects to the original beer that were clearly there to see, like hop character for example—it was clearly hoppy in the aroma and really assertively bitter.

There was clear Brettanomyces, almost lambic levels, and that’s another thing that just disappears over a hundred years. It was just mind-bending. It was an astonishing thing to taste to get that insight.

Because I’d been banging on about how Bretty and bitter these things were—but actually having one that confirms it felt like vindication. It was a very surreal but cool experience.

RA: What’s next for Epochal?

GY: The taproom I'm excited about. Having people come here would be big for me, because I like to make things that have a story behind them. When you're making beer like this, it's important to get the chance to talk to people about it.