Go To The Place Where You've Finally Found — The Laurieston Bar, Glasgow

Editor's note: On the 18th of October 2023 it was announced that the Clancy family has put The Laurieston up for sale. This article was commissioned several months before publishing, and we have decided to leave the piece relatively unchanged, so as to document the important role the Clancys have played within Glasgow’s beer and pub culture.

***

“I’m not really working, I’m just playing,” John Clancy tells me, his lips curling into a wide smile.

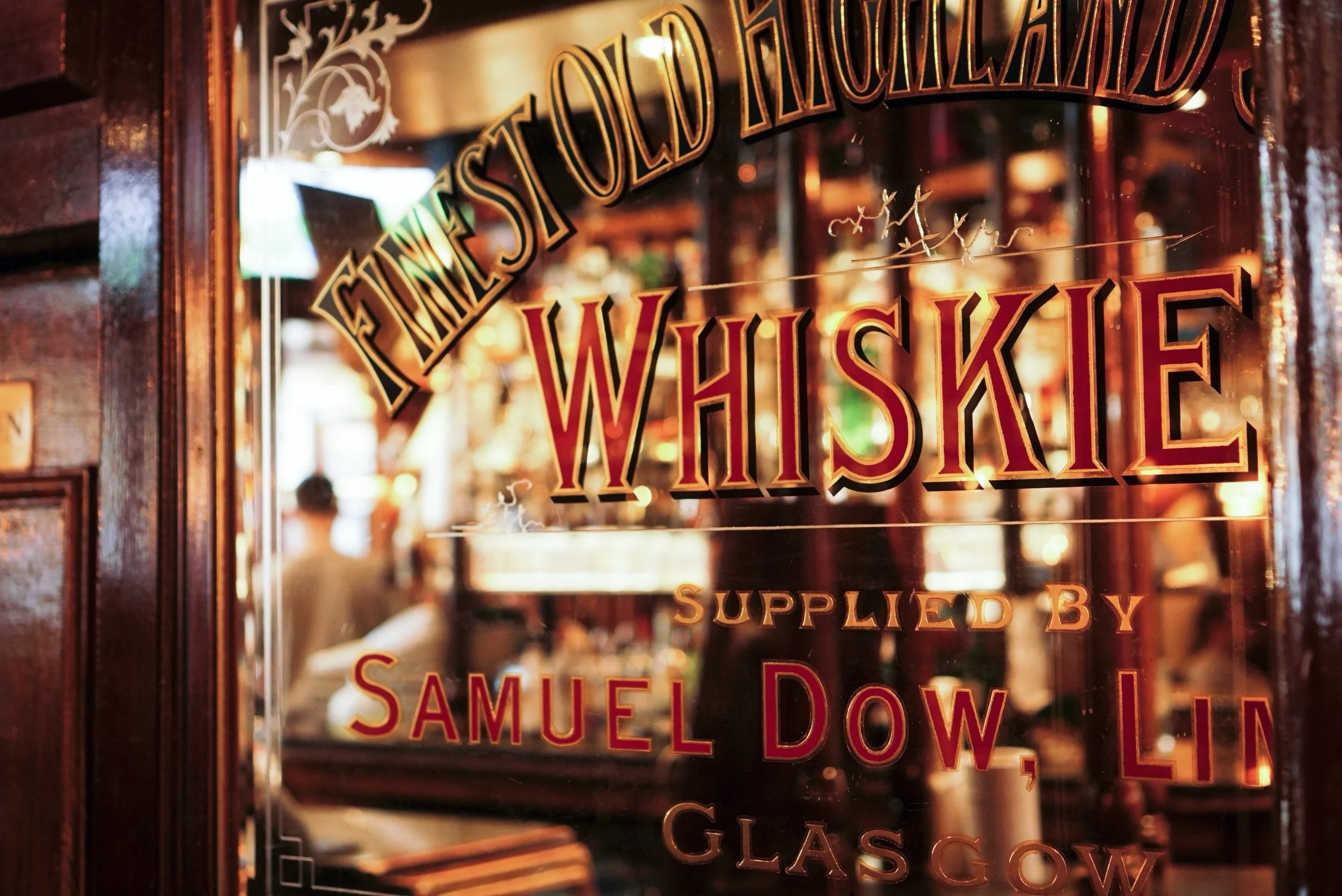

A septuagenarian with laughing eyes, black spectacles and a cheeky grin, John’s wit, sharp memory, and knack for spinning a good yarn aren’t what they once were, but he more than makes up for the deficit with his friendly demeanour, humility and trademark Glasgow patter. Like all great publicans, he even has his own catchphrase, emblazoned on a mirror in front of the main bar and known to all who frequent it.

A shopfitting joiner by trade, he’s been working behind the bar of The Laurieston in the eponymous area of Glasgow, just south of the river Clyde, for over half his years. He does so, like all the staff (a majority of whom are family), with a reverence for both beer and customer.

“I don’t worry about money, it’s the people that I think about, making sure they’re looked after,” John tells me.

His son Joseph runs the bar these days, having grown up behind it. He started working here, legally at least, when he turned 18 over two decades ago—but the picture on the wall of a bespectacled and smiling 12 year old, dish towel over shoulder as he polishes glasses, tells a different story.

Photography by Jonathan Hamilton

Like many of the Clancy clan, John and his brother James grew up running pubs. Their dad, also James, and their uncle Pat, ran The Happy Haven in north-west Glasgow’s Maryhill from 1960 to 1978, as well as The Rising Sun just south of here on Abbotsford Place. The brothers would go on to help run their dad’s pubs, as well as a good few of their own. They bought The Laurieston, now their only pub, in 1982.

As you enter The Laurieston, arrows point towards the public bar on the left and lounge bar on the right, both served by the same raised island bar. Most of the original furnishings are in a well-used but good condition, including red vinyl covered arm chairs, tartan curtains, custom red Formica tables, a raised gantry with wood panelling and a suspended canopy with built-in lights. The old McGee's hot pie heater sits to the right of the bar, a family heirloom serving hungry customers Scotch pies with a good lick of gravy and peas piled pleasingly on top. “A three course meal!” Joseph says with a wry smile.

The lounge is cosy, with dark wood panelling, red fabric banquettes, a tartan carpet, wood boxed ceiling and a jukebox that’s free to use. It’s no surprise the pub is listed in CAMRA’s Inventory of Pub Interiors of Outstanding Historic Interest, and Category C listed by Historic Environment Scotland, recognising buildings of “special architectural or historic interest which are representative examples of a period, style or building type.”

““You will not find a more genuine example of a friendly and inviting community pub anywhere in Glasgow.””

Even in a city full of them, this is one of Glasgow’s most welcoming pubs. When John’s brother James was presented with the Glasgow pub of the year award a decade ago, the CAMRA branch secretary Stan Thompson purred: “You will not find a more genuine example of a friendly and inviting community pub anywhere in Glasgow.”

Plaudits aside, there is something extraordinary to be gleaned from the ordinariness of enjoying a few pints at The Laurieston. This could mean nipping in for a quick, thick pint of stout, or staying until last orders, when the ring of the bell bestirs drinkers from absorbed conversation—a summons to order final drinks and soak up the atmosphere a few moments more. The more time spent here, the more the pub’s spatial and temporal dimensions contract and expand, shifting according to the intangible energy and collective mood of its denizens.

***

When it comes to beer, the choices at The Laurieston are many and varied, and not limited to: Tartan Special, McEwan’s 80/-, McEwan’s Export, John Smith's, Goose Island Midway, Cruzcampo, Innis and Gunn, Fosters and Amstel. Glasses for the lagers come straight out of the freezer, making pints look pleasingly frosty as they’re passed across the bar to thirsty customers.

Should you make the faintest enquiry about the real ale offering, you tend to be given a generous sample of them all, with the tickets pulled off the three hand pumps and placed carefully behind each glass as you taste. Jarl is the mainstay, with one or two other taps also from Fyne Ales on rotation.

“They're just letting the Jarl sing at the bar,” says Tom Hunter, a sales coordinator at Fyne Ales and Laurieston regular.

“It's pretty much a celebration of Citra hops, it's all about those grassy grapefruity, lemony flavours but it's still got a nice dry finish… so it leaves you wanting that next sip,” Tom tells me while nursing a pint of the stuff, adding that the bar gets through four firkins of it a week, equivalent to around 288 pints. “It’s a classic example of a modern British beer.”

Also on offer is Vital Spark, a traditional dark ale lifted with North American Amarillo and Cascade hops—which Fyne brewed alongside Hurricane Jack in 2010, using the same hops but different malt bills. The latter is a smooth, biscuity golden ale with a touch of tangerine on the finish. Easy going and moreish, it’s a far cry from its broodier brother. “You know the beer is in safe hands,” Tom says.

The Guinness here flows from three different taps: regular, extra cold and ‘the middle’, a somewhat clandestine vintage beer engine which looks ornamental at first, but is connected straight to the keg at cellar temperature, bypassing the modern python system. Joseph takes almost five minutes to pour me a pint from the middle, and it’s a sight to behold: voluptuous, nary a bubble, the dome’s surface tension appearing to defy gravity. It’s smooth, creamy, and coats my moustache as I gulp it down greedily.

When I ask Joseph about the quirk, he shrugs it off in self-effacing Clancy fashion. “People think what they want to think,” he says. Middle tap mythology aside, this is one of the city’s best pints of the black stuff, challenging the likes of Heraghty’s and The Brazen Head for Glasgow’s Guinness crown.

***

On a sunny day in early summer, I cycle past the pub to see John standing outside, watching the busy intersection as the traffic rushes by. He looks contented, even if the surrounding area appears to be conspiring against the pub, hemming it in with railway lines, lanes of busy traffic, abandoned buildings and overgrown gap sites.

The Laurieston district sits within the Gorbals, an area which has seen more destructive transformation in its history than any other area in the city. Today, redevelopment is reimagining the urban environment anew, this time at a human scale with balconies, gardens and tree lined avenues. In spite of all the upheaval The Laurieston (for now at least) defiantly remains a local boozer.

Regulars sit at the bar chatting to old friends, their coins piled up in wee towers on the beer mats for the cash-only till. The conversation flows from political discussions to chats about music, art, or just a wee bit of local gossip.

Davey, a friendly yet bashful man in his fifties, has been a regular here for twenty three years. He was born in the high flats on Caledonia Road, soon to be knocked down. Davey used to drink at The Queens Bar, run by James, on Queen Elizabeth Square, Basil Spence’s ill-fated brutalist experiment. Both were demolished, as well as The Rising Sun, John’s old workshop and much else besides, scattering residents and regulars out across the city. For Davey, this makes The Laurieston all the more important “to keep the tradition up.”

“It’s a great pub, everyone is made to feel welcome, no matter where they’re from—religion, background, it doesn’t matter in here… ye cannae beat it,” Davey says.

***

On a rain-soaked afternoon towards the end of June, John is showing me around and recounting the history of the place. His eyes sparkle as he takes my arm, pointing to pictures of the family’s old pubs from the sixties and seventies: the long-demolished Commercial Bar near Celtic Park; a figure clutching a lamppost in front of The Happy Haven; brothers Pat and James standing proudly with beaming smiles alongside their staff at The Rising Sun. There are scribbled notes underneath photographs of family members and friends, while hand-drawn maps show where the old pubs used to be, once nestled into the hearts of their communities.

The walls are papered with history: photographs depicting Glasgow in black and white with horse-drawn trams; newspaper cuttings; signed and illustrated beer mats; various keepsakes of the family’s old pubs, from paintings to old invoices for kegs of Tartan Special; mementos to those they’ve lost over the years. The memorabilia has a transporting effect—the more you look, the more the space reveals itself as a working people’s history museum of the Gorbals in all its rich, dense and multitudinous indomitability.

“ “We treat everyone the same, there’s no difference—we want it to be for everybody.””

The pub looms large in popular culture, from Scottish comedy Still Game to 2003’s Young Adam, set in 1954 Glasgow and starring Ewan McGregor, Tilda Swinton and Peter Mullan (there’s a framed 35mm reel from the film in the lounge). The bar stood in for a Dundee boozer in Succession, in an unforgettable scene in which Roman Roy accidentally agrees to buy Heart of Midlothian F.C.

Big names are reduced to regular punters: Frankie Boyle, David Hayman, Shane McGowan, Saoirse Ronan, Jack Lowden—they’ve all been in for a quiet drink or two.

“People don’t bother them, they’re left to their own devices—folk are like: ‘they’re in for a drink, gie them peace!’,” Davey says.

I once saw comedian Joe Wilkinson having a quiet drink in the lounge, any hint of celebrity somehow incongruous with the vernacular surroundings. “Absolute belter of a pub… More characters than a computer keyboard,” wrote Ian Rankin after a visit earlier this year.

***

Cycling home through the Gorbals redevelopment one afternoon, I stop at the area’s last remaining tenement, 166 Gorbals Street. An art nouveau former British Linen Bank, built in the Glasgow Style, it had lain empty for a generation until a major refurbishment began in 2015. The red sandstone facade boasts pristine decorative ironwork, asymmetric windows and intricate stonework, smoothly integrated into the modern flats on its south flank. Fittingly, the building’s architect James Salmon saw life as an infinite flux of generation, degeneration and regeneration.

On the north gable’s sculptural framework there is a quote from Salmon: “The art in a building would always reflect that period or moment in the continuum of time when it was conceived and realised.”

166 Gorbals Street and The Laurieston both serve as important tangible links to the Gorbals’ past and present—helping Glasgow make sense of its history amid so much cyclical change. There is a vestigial charm to drinking in The Laurieston, one of a diminishing number of traditional Glasgow boozers, and one of the few remaining parts of the Old Gorbals, alongside The Brazen Head and Caledonia Road Church.

The Laurieston is often described as a ‘time capsule’. I disagree. Timeless, perhaps, but not frozen in time; it is always subtly shifting to meet the needs of its community, standing proudly in the face of so much urban churn not because it is petrified in the past, but because it is deeply attuned to the lives of its customers—themselves in a steady but perpetual flux.

“You've got characters from all sorts of walks of life, all sorts of social, economic backgrounds, all sorts of ethnicities—it's just a really welcoming place and they sell real ales as well … but it's not a real ale pub—it's a pub that sells real ale,” Fyne Ales’ Tom Hunter says.

“[The Laurieston] encapsulates the spirit of Glasgow… It really just embodies that real spirit of everyone’s welcome here,” Tom adds.

I ask Joseph if there’s another generation ready to take it on after him.

“It’s hard to say what’s round the corner, there’s nieces and nephews, it all depends if they want to take it on. There might not be any pubs then, the world might be ending by then. You never know.”

When I ask him what’s most important to him about the pub, he tells me it’s that the customers are like family. In recent weeks they’ve written cards for regulars celebrating their 40th, 60th and 70th birthdays.

I ask his dad how it has endured for so long. “We treat everyone the same, there’s no difference—we want it to be for everybody,” John tells me.

***

As I’m putting the finishing touches to this piece, it’s announced that John and James have put the pub on the market, in order to devote more time to serving the family that’s kept this family business going for over forty years. For the first time in decades, the future of this iconic pub feels unknown. One thing’s for certain though—the Clancys have put in a shift that places them comfortably in the pantheon of Scottish publicans.

The Laurieston has embodied, perhaps better than anywhere else, the spirit of this ever-changing city. It’s all here: the humour, the grit, the joy of talking to complete strangers, the love of a good drink. This is a pub that serves nice beer, sure, but it is much more than that; it is a place that has been shaped, through call and response, to the lives of the like-minded, disparate people who drink here. Or maybe it’s just a pub.