What’s Worth Keeping — Macintosh Ales in Stoke Newington, London

There’s a small yard a moment away from Stoke Newington Church Street in North East London. At its entrance an entirely perfunctory and heavily battered railing protects the square of overgrown cobbles from the pavement beyond. On the first floor of the old stable buildings on three sides, four green doors lead to nothing but a 10-foot drop; the yard is hemmed with various shades of green paint—faded and flaking patchwork grass, darker, glossier army-surplus vehicle paint. But for a hand-painted sign and a number of planters giving the game away, passing on a quiet morning or late at night it might look a little tired, unloved.

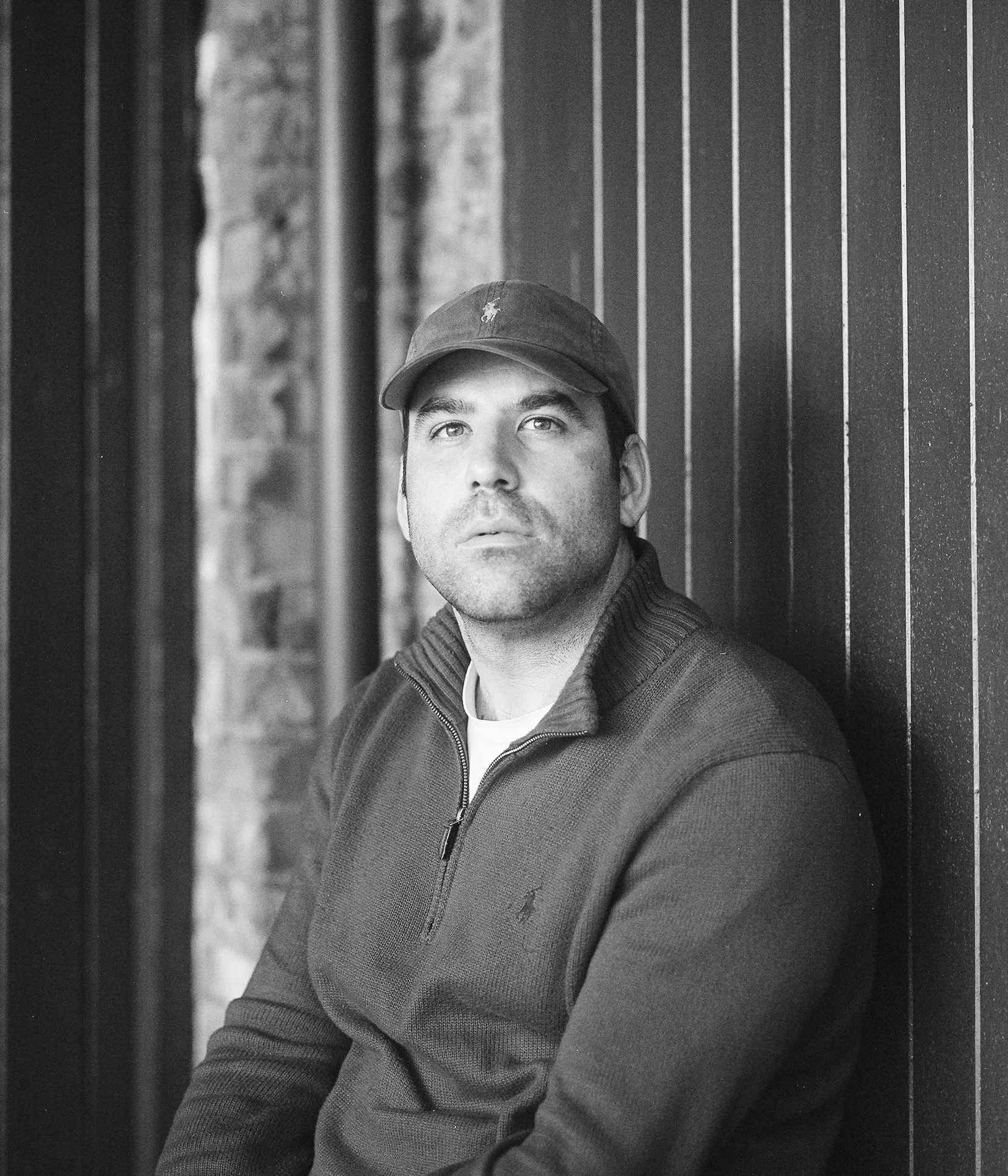

Photography by Lily Waite-Marsden

Stroll by on a warm summer’s evening, or on a Saturday lunchtime, and there’s a complete transformation. A hair salon on the corner of the yard, artists’ studios on one side with plastic-wrapped prints and paintings on display, and on the other is Macintosh Ales and its ale house: a small drinking space, a warehouse, a “function room.”

The ale house is at once a familiar, nostalgic space, and an anomalous one. A simple, small room with walls in a two-tone of brown and cream and a short central bar with a deep mustard front and mahogany top, it’s furnished with second-hand and vintage effects. Settle on the velvet-topped barstools either high and low, the long, punitive wooden benches, a salvaged church pew; rest your pint on the dense, iron-bottomed round tables that pepper the space.

A tall cabinet with a curved front (sourced painstakingly from Facebook Marketplace, owner Charlie Macintosh proudly told me the day we first met) stands sentry in one corner, displaying bottles like collected trophies. I saw him once this summer, heavy stable doors in the back of his van, after he’d driven for hours to collect them after purchasing them online. A gleaming brass footrail, rescued by a regular from a closed pub provides something “to do with your feet,” as Charlie wrote on Instagram.

Much of his social media presence is detailing small additions to or highlights of the alehouse’s aesthetic or function: ledges the perfect width for a pint glass as detailed in a 1950s guide to pub interiors; the original drawing of the brewery’s logo drawn by his brother years ago now hung behind the bar; an early photograph of a bottle of pale ale amidst bread and cheese bestowed upon the wall of the toilet. Nothing of new beers or events, just “open from 4pm” or “have a great week, thanks.”

A mix of signs, all from various pubs, inform you “we serve you with the greatest pleasure and the finest ales,” or—previously—advertised the ale house’s menu of “CRISPS, PORK PIE.”

The ale house is not a bar, not a pub, not a taproom, although it is often mistaken for each. It is peculiar—certainly when held up for comparison to arguably every other drinking establishment that opened in the last five years—but therein lies its appeal. It’s different.

““Ale is a word that puts off most people; they’re terrified of the word.””

“It's very hard to make a pub,” Charlie says. “And ‘ale house’—what does that mean? But I didn't want to call it a bar, because that sounds like we're in New York. It's not a bar, because our peak hours are 4 till 7.”

It’s not a taproom, dilute as that term has become, because Macintosh’s beers—ales—aren’t brewed onsite, or even in the near vicinity. It’s not a pub, because, well, it isn’t.

“The reason I called it an ale house is because we don't make a lager. So I thought that saves an easy question for everyone that walks in and wants a lager. Ale is a word that puts off most people; they're terrified of the word. And there's something weird about a new pub.”

Apart from customers crowded close on a busy Friday night or a regular and their book on a Sunday afternoon, the ale house’s bar is home to three things: a well-polished hand pump, a keg font, and one of a rotating selection of vintage bar towels.

The beers never change: Macintosh Best Bitter on the pump, Macintosh Pale Ale on tap. You can get a glass of wine if you wish, or a soft drink. Until Charlie’s recent foray into haute cuisine with the advent of a toastie maker you could order crisps, or a solid and meatily gratifying half a Melton Mowbray pork pie, served with Colman’s mustard.

The entire outfit is delightfully simple—no menu, no decision paralysis, no frills, no faff. It rejects the contemporary compulsion to be at once everything to everyone, to exclude none by covering all bases. It is simple, and oddly remarkable for it. It is special.

***

The story of Macintosh Ales is, at first glance, so familiar within the beer industry as to be dull. A charming middle-class man took up homebrewing, discovered both a love and a talent for it, and scaled up. He brewed in a garage, sold beers across his local area, and grew demand. A brewery was born, and the beers well received. It is the tale of the majority of small breweries in the UK.

Yet this is not a story of a medium-scale modern brewery making the de rigeur styles of today’s market: Charlie wasn’t interested in the latest US hops, nor hazy IPAs, nor in tap takeovers across the country, nor rapidly scaling production. His best bitter and his pale ale are the only beers he’s brewed in six years; they only use Norfolk barley and Kentish hops. They are not revisionist contemporary takes—they are well-executed, delicious, and rather classic iterations of their respective styles.

““The most English of things is cask beer, and it’s mad, there should be queues down the street for it. It’s so stupid that there aren’t.” ”

Macintosh began in Charlie’s dad’s house on a basic homebrew kit. “My dad has a garage at the back of his house in Hammersmith,” he says. In September 2018, he turned that into a brewery and put a 500 litre kit in it. “I feel very, very lucky. The fact that my dad let me brew in his garage was pretty mega.”

Before this, Charlie worked at the now-closed restaurant Lyle’s in Shoreditch, which further cemented his interest in and love for food and drink, particularly British produce and producers.

“I just loved it,” he tells me. “But I always was like, in my head: we celebrate all these things so much. But for me, the most English of things is cask beer, and it's mad, there should be queues down the street for it. It’s so stupid that there aren’t.”

***

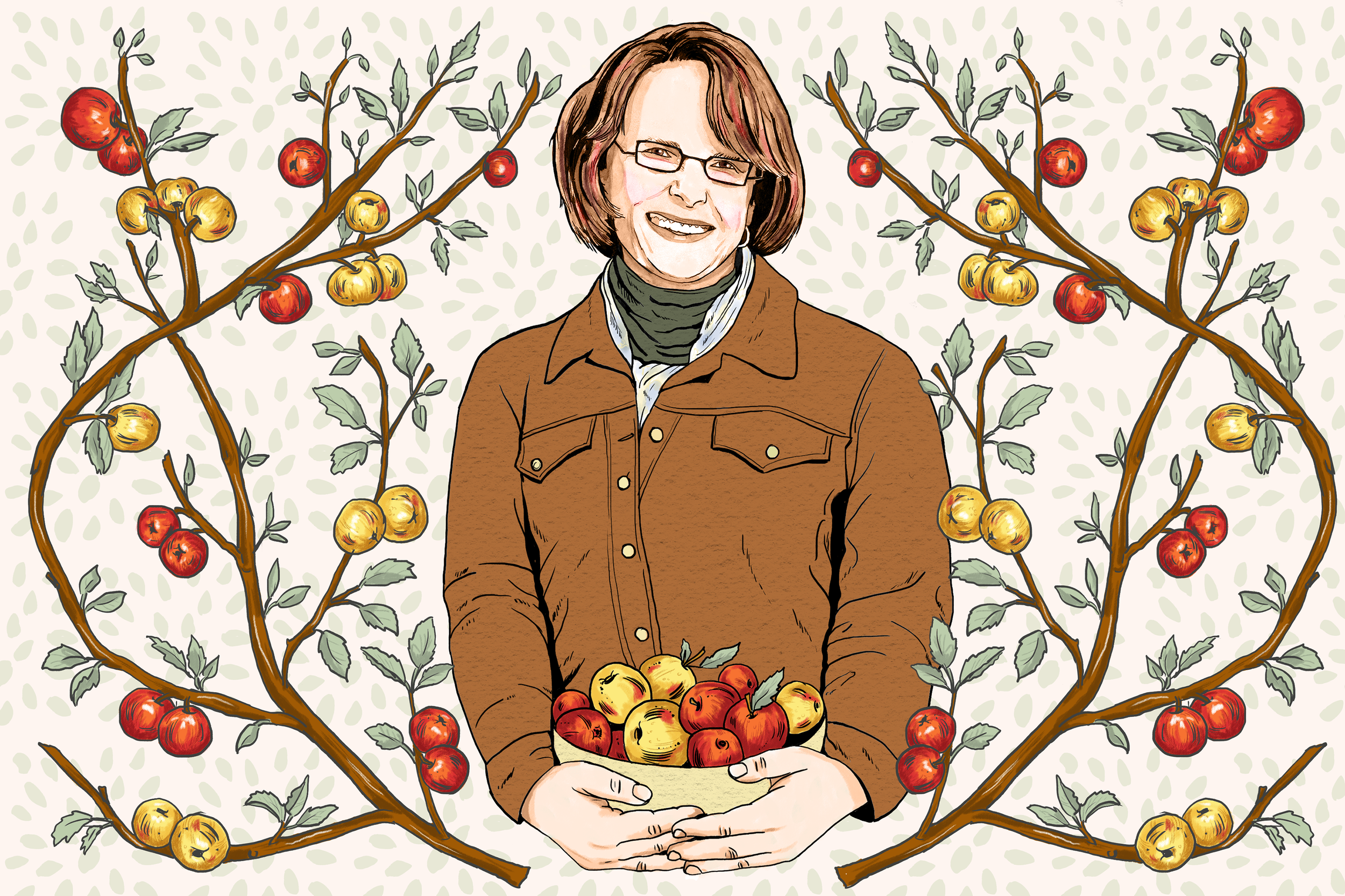

“I don't know who first told me about his beers, but he had connections to the hospitality world and so word got around that there was this guy brewing his own beer on a super small scale in London,” Nathalie Nelles, wine director of Goodbye Horses, a wine bar in London’s De Beauvoir that serves Macintosh Pale on draught. Nathalie was one of the first people to stock Charlie’s bottles “five or six” years ago, at Noble Fine Liquor on Broadway Market.

“The things that are important to me when it comes to food and beverage are largely about provenance, small scale, sustainable production,” she says. “People who do stuff with care and with their hands. I just want something really well made that feels kind of timeless and delicious, and speaks to the person and the place that it was made.”

Charlie, whose beer to Nathalie remains unchanged after all that time, spoke to these ideas, and the beers reflect his own inspirations and the importance of ingredient choices, of provenance.

“I think for certain communities of people—and Charlie's firmly in that community—these are things that we care about,” Nathalie explains. “When you work in restaurants that really give a shit—when he was at Lyles, he was working with Nominoé Guillebon, who was the former sommelier there. These are conversations that you end up having over and over again when you work in good restaurants, so I'm sure some of that rhetoric seeped in.”

In Macintosh Ales’ formative years, all Charlie brewed was his best bitter, and only a small volume at that, refusing to listen to those who told him to brew more—something he attributes (negatively) to stubbornness, something I view more as singular dedication. “If I’d listened to people, I would never have got here. Honestly, back then when I told people I was making a best bitter, people fell off their chairs laughing.”

Brewed with floor-malted Maris Otter and whole-leaf Fuggles and East Kent Goldings from Hukins Hops, it is a perfect tightrope dance of malt and hop character: gentle caramel wrapped in date and plum on the expectant inhale; a confident and affirming bitterness darts between floral, fruity esters and a rich, honeyed juiciness from the malt.

The first casks from Charlie’s dad’s garage were sold to the Southampton Arms. Charlie was drinking in the pub and got chatting to then-publican Nick Bailey. “He was like ‘yeah, we'll take, what, three?’ And I said ‘I've only got two.’”

“I used to see this bloke—he used to just come in and tell me about his beer,” Nick, who opened his own pub The Robin in 2023, says. “I didn't really pay much attention; I get so many people telling me about their beer. But there was something about Charlie that, in the end, I was like ‘fuck it, let's give it a try.’”

“It was really, really good. I remember when we put it on, he brought his dad, and—I don't know—I felt something akin to pride. I had this strong feeling for him and his beer. It felt like a very special moment.”

***

When Charlie opened the doors in 2023, the ale house was quiet. “When I first opened it was only family and friends that came,” he says. “For the first year, really, nobody came.”

I first visited on a Saturday in November that year to find one or two locals enjoying a beer and others curious like me to see what this cupboard-like pub was. The ale house is now Macintosh’s almost sole focus: it’s steadily busy across its opening hours and often full to bursting on Friday or Saturday evenings.

“I feel really lucky sometimes when I'm there on a Friday night and it's rammed, I just look around and go, ‘I don't know any of these people,’” he says, a stark contrast to that first year. “There's like 20-year-olds that if you go online, they just say they sit in their bedroom and play PlayStation. But they're here drinking bitter. 20-year-old girls drinking, playing darts. It's quite amazing to see. Like really, really lovely.”

Although the ale house has grown busier and its popularity has increased—at times, almost problematically—Charlie’s never stopped appreciating those for whom the beer means less than time spent with friends, or just the space itself.

“We get a lot of people that are really into something;” he says, and for some customers, that’s rarely the tasting notes or ingredients. Charlie’s proud of that.

““There was something about Charlie that, in the end, I was like ‘fuck it, let’s give it a try.’””

“I think it's a really big pat on the back when people don't need to analyse the beer,” he says. “They just want another pint, and another. Someone’s had five pints and they haven't needed to say something's good or bad—that’s a great thing.”

On my latest visit, a buzzy Saturday afternoon—Charlie’s mistakenly turned up for the opening shift, and regulars chat perched on barstools as the outside benches ebb and flow—both beers are tasting delicious. This latest batch of bitter is bright and satisfying, the pale, brewed with lightly-kilned Maris Otter, which, like the malt for the bitter, comes from the Maufe family on Holkham Estate in North Norfolk, and hopped with Keyworth’s Early, also from Hukin’s, is zippier, lighter, with a declarative bitterness supporting lemon and grapefruit notes, with just a little floral pop. It, like its sibling, is resoundingly English in style, and is the kind of simple that belies dedication and intent refinement.

“He's very finickety about things. It's a beautiful trait to have, you know,” Nick says. “You'll be lucky if you're born with that, taking care of the smallest detail. That's why the ale house is like that. If he wasn't like that, the place, the beer wouldn't be as good as it is right now; it's exactly because he's very particular about what he does. You end up with this beautiful thing that he's created and this amazing beer that he has.”

***

I first spoke to Charlie for this piece in September 2024. At the time, the ale house had just enjoyed its first busy summer, and production was a concern: he’d begun contract brewing his beer (briefly, at the now-closed Solvay Society in Walthamstow, then Orbit in Camberwell, where it’s still brewed) in 2021 and had more recently begun to confront the varied challenges that entails: the incomplete control over the product, the lack of flexibility and ability to respond to sales trends, constrained production volume. He brews one 40hL batch a month, but he “would take two pale slots a month if we could get them,” he said. “And then the bitter, we’d do that again if we could. But we can’t.”

I met with him again at the start of October this year (during which he repeats his bemusement at my interest in writing about him and Macintosh Ales—something both Nick and Nathalie ascribe to Charlie’s deep care for what he does giving rise to a confusion that more people don’t simply do things like him; that level of care is to him very normal and not in some way noteworthy).

When we speak, he’s waiting for the lease on a brewery site in Finsbury Park, “kind of everything I pictured when I thought about it years and years ago,” that he found after viewing over 20 potential spaces over the past year. (He worriedly texts me, a few days later, to say the landlord has gone quiet.)

His plans—which, although he’s found his flooring contractor and some second-hand tanks, hinge upon securing the space—are simple (as simple as building any new brewery can be.) He wants to brew the same two beers, perhaps with the odd new release here and there, but with full control over the process and the ingredients, and to be able to meet demand beyond the ale house.

“We’ve had to scale back massively from last year. We do very, very little wholesale now, only to a handful of customers,” Charlie says. “It means when you’d have a dip in the ale house, like previously in the winter months, we would go ‘Oh, we can scale up cask to pubs.’ But we haven't been able to do that now, so I'm really looking forward to next year, where we’re in control: this year's been really good, but very, very hard. It always feels like we're playing catch-up, and never, ever felt like we were in control of everything that we want to be.”

For a brewer who for the fledgling years of his career brewed, packaged, and distributed his beer himself, the loss of connection to the beer contracting inevitably brings has been challenging. For someone with a background in ingredient-focused restaurants, who cares deeply about the provenance of his beer, it’s difficult.

With his own brewery “we can do it all, and be in control over ingredients, too—it’s a very wanky phrase, but—literally from grain to glass.” Brewing enough to sell to pubs and bars in London, making those deliveries and speaking to publicans, will help reestablish the links in that grain-to-glass chain, strengthening Charlie’s relationship to the product. But his first aim, in his own site, is just to brew enough beer, and make it really, really good.

Contract brewing is never easy, but for Charlie it’s made harder by virtue of the conditioning required for both beers: two weeks in keg for the pale, three to four weeks cask-conditioning for the bitter. It’s an age-old coin-toss: accept that brewing your beer your way, but on someone else’s kit and at the mercy of their schedule will never meet all your needs, or compromise, settle.

“Do we just sacrifice what we are and essentially churn out lesser quality beer?” asks Charlie. “Once we sacrifice that, then where do you draw the line? You've got to stand by something, haven't you? Otherwise, what's the point?”

***

I’ve spent a lot of time in the ale house. I’ve introduced countless friends to the pale or bitter and bumped into others unexpectedly when calling in after walking my dogs in the cemetery nearby—a quick half turning into an hour or two and a couple of pints. I know regulars to nod at, though I largely keep to myself, save for ambling chats with Charlie, or Rory or Harry, his two employees.

To imagine any permanent sense of community in any drinking space would be fantasy, but here when that often-present feeling dwindles in its place remains a familiarity, a conviviality. Though small spaces such as these can be exposing—to sit in a quiet pub under the ever-watchful gaze of an under-tasked bartender can feel disquieting—the ale house always feels welcoming, and warm.

A small, simple space may not feel out of place in the wine world, or operating as a cosy, intimate restaurant. But it does stand out amongst beer spaces—bars, pubs, taprooms—where proprietors offer a wider range of products to cater for broader tastes. Aesthetically, visually, even purposefully, some feel timeless by virtue of age, others contemporary, and some in the awful uncanny valley between the two where lie many ruined pubs. But few, very few, are created with such consideration and such character—certainly in the ale house both of these traits are true reflections of, simply, who Charlie is. That, it seems, is the draw, often more so than the beer itself.

“I think one thing that is really amazing about Macintosh—and that ends up being reflected in the ale house, and the people that frequent it—is that he's created something that's so timeless in the sense that it defies trends, or categories of people that might like it,” Nathalie explains. “If you spend time at the ale house, he's got such an incredible mix of people coming for something that could have been really usurped by it being a trendy new pub. He's got all demographics in there.”

“That also speaks to Charlie’s way of just being able to get on and chat with anyone,” she continues. “But I also think the style of the beer is such that it doesn't alienate anyone: it just speaks to people across all sorts of social, economic, race, class divides. It’s just beer for everyone. And I hope that people get it as much as I get it—but I think all you have to do is interact with it a couple of times to get it. That's kind of the magic of Macintosh.”

Those that get it really do seem to feel that magic; this is almost-tangibly evident when spending a while on a church pew with a quiet pint, or tucked into a corner by the swell of an evening.

“I think Charlie feels he's very lucky to be doing what he's doing, he's very lucky to do for a living something that is close to his heart and close to who he is as a person,” Nick explains. “There's a bigger goal than just, ‘Oh, I want to make money.’ That shows in there, in what he’s done, and the environment that he's created—and that resonates with other people.”

In both interviews Charlie makes clear the lack of financial motivation behind the six-year span of Macintosh Ales, first by suggesting he might otherwise sell buttons in bulk, later that he’d just buy a buy-to-let flat and collect rent. “We would make loads more money if this was a negroni bar or a wine bar, right? But I'm not driven by money: I suppose I'd just have been selling something on eBay or Amazon or something. I just want—I don't really care how many people there are, who they are, but—someone, somewhere to care.”

It’s abundantly clear that people—many of them, all crossing the threshold of a small room in Stoke Newington—do care, even if their demonstration of this, like Charlie’s, is quiet. “My favourite thing about the ale house, sometimes” he says, “is when we say to people: ‘What are you up to tonight?’ And they're like ‘Oh nothing, I'm staying in.’ But they're here.”