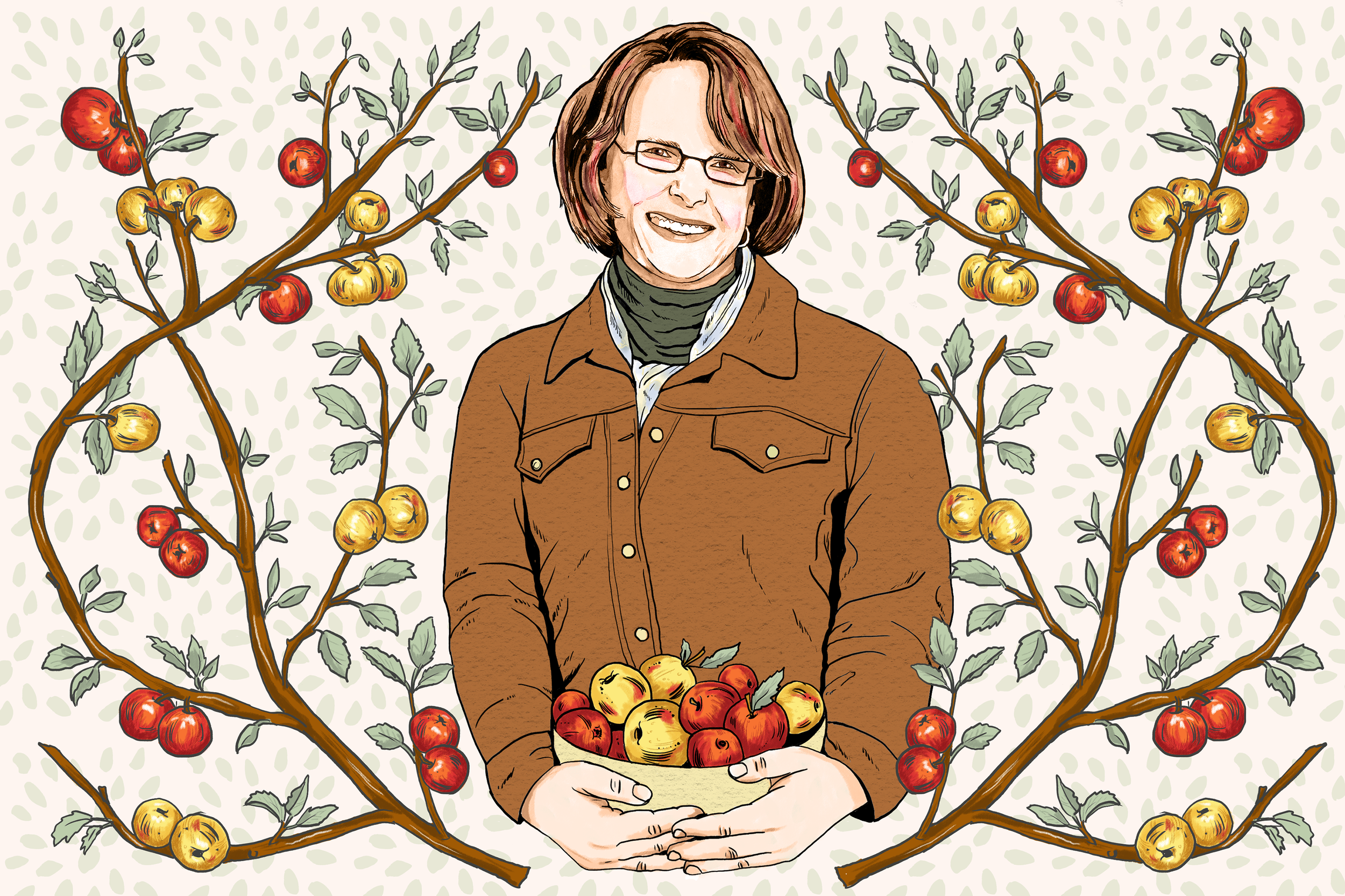

Apple Tree Woman — Diane Flynt and Foggy Ridge Orchards in Dugspur, Virginia

“Before there is cider, there are apples,” is a common refrain during my time spent in the far southern marches of Virginia with Diane Flynt, founder of Foggy Ridge Orchards and a pioneer of the cider industry in Virginia. It is a phrase I have returned to and mulled over many times since I first spoke with Diane through the delightful medium of a Zoom call back in early 2024 while I was researching my book: Virginia Cider: A Scrumptious History.

When meeting her face-to-face, I eschewed the dense, heavy, traffic of Interstate 81 in favour of country roads meandering their way through the Piedmont and Blue Ridge Mountains. It felt appropriate, somehow, to wind my way through the heartlands of the apple in modern Virginia rather than whizzing down the freeway, just to save ten minutes of driving. It was overcast, with the promise of thunder, as I dipped into the holler near Dugspur where Diane established the first commercial ciderworks in the South since Prohibition.

Before there was a cidery, there was a career in banking that Diane wanted to escape. In 1995 she and her husband, Chuck, bought an old farm in Dugspur, Carroll County. About 20 miles as the crow flies from the state line between Virginia and North Carolina, Carroll County is dominated by the Blue Ridge Mountains, which form part of the Appalachian Highlands. Rising to about 3000ft (900m) apples have long been a key part of the economy in these parts. Diane’s intention in settling among the mountains and mists of Appalachia was not to just homestead for her and Chuck’s own table. She wanted to create a successful agricultural business.

In November 1997, Diane and a neighbour planted the first trees of what would become Foggy Ridge Cider, now known as Foggy Ridge Orchards. The 250 trees were drawn from 35 different varieties, including many that had been hanging on by thread, remembered and guarded by a dedicated few. Among those first trees were Harrison and Virginia Hewe’s Crab—a variety that pre-dates the American Revolution by at least 60 years and is, in the minds of many a local cidermaker, the defining apple of Virginian cider.

Illustrations by Chantal Bennett

Six years later Diane and her crew would harvest, scrat, and press the first drops of juice that would become Foggy Ridge Cider. In their 14 years as a cidery they would peak at producing 75,000 bottles a year, sold in 25 states. Even at the height of their cider production, Foggy Ridge was only buying in around 30% of the fruit they used, largely due to Diane’s belief that “there’s no reason to grow what you can readily buy from those around you.”

***

Sitting on the patio overlooking the lush verdant slopes of the orchards, the creek—from which mist rises in the morning, the inspiration for the cidery’s name—in the distance, Diane and I talk about apples, farming, and the making of cider.

“It’s not just apple cider varieties—that’s one thing—it’s apples grown for cider,” she tells me. “When I bought Goldrush, I paid in advance for my apples and said ‘I will buy every apple on that tree, but I do not want you to pick them until they are falling off the tree.’ That’s growing apples for cider—they have to be dead ripe on the tree.”

Central to Foggy Ridge’s success in re-establishing cider within the minds of drinkers throughout the American South was Jocelyn Kuzelka, Diane’s cidermaker from 2010 until the final vintage flowed from the presses in 2017. With a background in wine, Jocelyn returned to Virginia from Australia in 2008 to take over her family farm in the next county over from Foggy Ridge It was as a consultant that she first entered Diane’s orbit, primarily focused on product development. When Diane decided to focus on producing quality cider apples exclusively, Jocelyn continued her own cidermaking journey on her own farm, establishing Daring Cider Company in 2021.

““I paid in advance for my apples and said ‘I will buy every apple on that tree, but I do not want you to pick them until they are falling off the tree’.””

“[Diane has had a] huge influence, both as a woman in the industry and as a cidermaker, even thinking about what were the possibilities for myself, and that has grown into Daring,” Jocelyn tells me. “She has shown me that women can do this, be successful, and be respected.”

One particular area of Jocelyn’s own cidermaking philosophy impacted by Diane is a focus more on blended ciders at the expense of single varietals.

“One thing with Diane that was always a little bit different is that she was more of a blender,” she adds. “Having an orchard of 30 varieties, it can be difficult to make a single variety of each one for years and years. Her influence is ‘yes, let’s talk about the apples, but let’s make a delicious cider,’ and each year make each blend as good as it can be. We always used good cider apples, and honed the blend to make the best cider we could.”

Clearly this approach, focusing on making delicious cider, is paying off for Jocelyn and Daring Cider, as their Crab Apple blend, a—frankly—sublime marriage of Virginia Hewe’s Crab and Ruby Red, walked away from the 2025 Virginia Governor’s Cup with the title of Cider of the Year.

Diane’s influence on Jocelyn doesn’t end with the focus on blending juices to make a more harmonious whole, but also to the conviction that it is better to have an orchard where you grow the things you cannot buy locally.

“The agricultural part of cider has been lost overall in America… unfortunately it’s become more about your tasting room and your view, and less about the fruit, less about the farming, the dirt,” Jocelyn says. “I’m proud that I buy great quality cider apples from orchards because if I didn’t they would literally end up on the compost heap because we have an apple glut. We are losing [for example] Newtown Pippin orchards because it is not being used.”

Jocelyn is convinced of the importance of the orchards, and the agronomics involved in producing high quality cider apples for the production of equally high quality cider. Whether it is maintaining soil nutrient levels, the annual task of pruning, or how you control disease and pests, at the heart of all cider is good apple husbandry.

“Because Diane grows her own apples, she understands that it is a long term game, and that’s where the focus on quality really comes from,” Jocelyn says. “She’s not just in it for a quick buck, the goal is to develop something that lives beyond our time here.”

Another drawing on Diane’s powerful belief in the primacy of the orchard in cidermaking and the importance of a sense of place is cidermaker Will Hodges of Troddenvale, in Warm Springs, Virginia. In common with Foggy Ridge, the world of Troddenvale is mountainous, with a creek running through the historic farm that has been in Will’s family for generations.

The orchard at Troddenvale differs from many other plantings in Virginia in that Will, and his wife Cornelia, identified geographic analogs in terms of their terroir, elevation, and climate with the Asturias region of Spain, and wanting to grow fruit others either can’t or aren’t dabbled with Asturian varieties such as Coloradona, Piel de Sapa, and Solarina.

““We always used good cider apples, and honed the blend to make the best cider we could.””

“[Spanish apples] are some of the most productive apples in the system, and they make great cider, leaning more to acid than tannin,” Will tells me.“Style begins in the orchard, it’s here that differentiation is developed, and identity grown. The focus is on what it means to grow fruit in Warm Springs, Virginia, and to always focus on what grows well in your climate. ”

Diane also has a much more direct influence over Will’s cider maker as Foggy Ridge has become a supplier of apples to Troddenvale. Such is the reputation of Foggy Ridge, that cidermakers from around the South, not just Virginia, are keen to purchase her fruit to include in their blends. In the early years of purchasing from Diane, Will admits he kind of just had to take what he could get, until they developed an understanding and deeper relationship.

It was during the early relationship with Diane that Will had the opportunity to indulge in his love of acidic apple varieties, such as Parmar—an old Virginia variety that allegedly makes an excellent apple brandy.

“[Parmar] ripens at the end of July, and Diane will only sell if we can be there on time for the fruit to be at its peak as apples for cider,” Will says.

There is a tradition in the West Country that the oldest tree in an orchard is inhabited by the spirit of the Apple Tree Man. It is Apple Tree Man that is responsible for the ongoing fertility of the orchard, and is the focus for the folk custom of wassailing, anointing the roots with cider and hanging bread in its branches.

Here in Virginia, we have Diane Flynt, the guardian spirit of orcharding specifically for cider, and the well spring from which so much of the cider renaissance throughout the South has come.

“The future of cider depends on orchardists growing cider apples and apples that are good for cider,” she tells me. ‘I don’t think that’s an exaggeration.”