Under the Bridge — A Definitive History of Wychwood Hobgoblin

My love affair with pubs started in Staines. It’s where I found my tribe—the pub as an expression of individuality, an alternative to bland Britain. But I was afraid at first.

In 1996, my British-Asian father and I stepped into the pub fearing the worst. Sepia-stained walls. Tan tables. Nut-brown floorboards. Eyes staring at us from around the room.

For a brief moment it felt like we’d stumbled upon a hostile, 1970s working men’s club, but before we could turn around and head back out, some familiar lyrics filled the space.

“Step into a heaven where I keep it on the soul side.”

Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magik was pumping out of the speakers. This was the first time I’d been in a pub and heard what I considered to be real music instead of middle-of-the-road commercial radio or stilted silence.

I was 18, and Staines felt like the fag-end of drab Britain. My dad nodded, a rare bond forming momentarily between us. I’d been begging him for weeks to take me to this “rock pub” I’d overheard people at my sixth form talking about. When we arrived, we quickly realised it had been worth the 40-mile drive.

Looking back from the technicolour glare of 2025, the decor may have seemed muted, but what was offered at the bar was like a dream, with one beer standing out proudly from the rest. Among the traditional porters and bitters was the ruby beer that shared the name of the pub: Hobgoblin.

The pump clip was like nothing I had seen before, with a boldly realised gargoyle-esque character, so different from the others that were just plain red or green. My dad bought me a half; it was stronger and sweeter than other beers I had tasted in my nascent drinking days. He had an even stronger beer, which was irreverently called Dog’s Bollocks. I definitely detected a hint of bashfulness when he ordered it.

Looking around, I saw people with tattoos for the first time. It wasn’t the norm then—or at least it wasn’t my norm. I liked it. This was a scene I wanted to be part of.

“Seeing the Sex Pistols’ album Never Mind the Bollocks in 1977 in shop windows was really shocking,” author and journalist Jeff Evans tells me. “Seeing a beer called Dog’s Bollocks in the early 1990s was [also] shocking and provocative because it had never been done before.”

***

“BrewDog is a modern interpretation of Hobgoblin,” says James Coyle, who was sales director at its parent brewery, Wychwood. “[The Hobgoblin identity] was built on motorbikes, grunge, and tattoos—this was the escapism of the brand.”

Established by Paddy Glenny as The Glenny Brewery Company in Witney, Oxfordshire in 1983, it was renamed the Wychwood Brewery in 1990. Somehow, this small brewery in rural Oxfordshire went from selling to a few freehouses to producing a beer so iconic that it shifted 100,000 barrels a year, changed pub culture, and eventually became a global brand in the Carlsberg portfolio.

Thanks to breweries like BrewDog, today we’re used to shock marketing tactics from beer firms. Many of the people I spoke to while researching this article repeated James’ sentiment about Hobgoblin being akin to the often-controversial Scottish brewery, including the fact that its initial success was driven by word of mouth rather than a huge marketing budget.

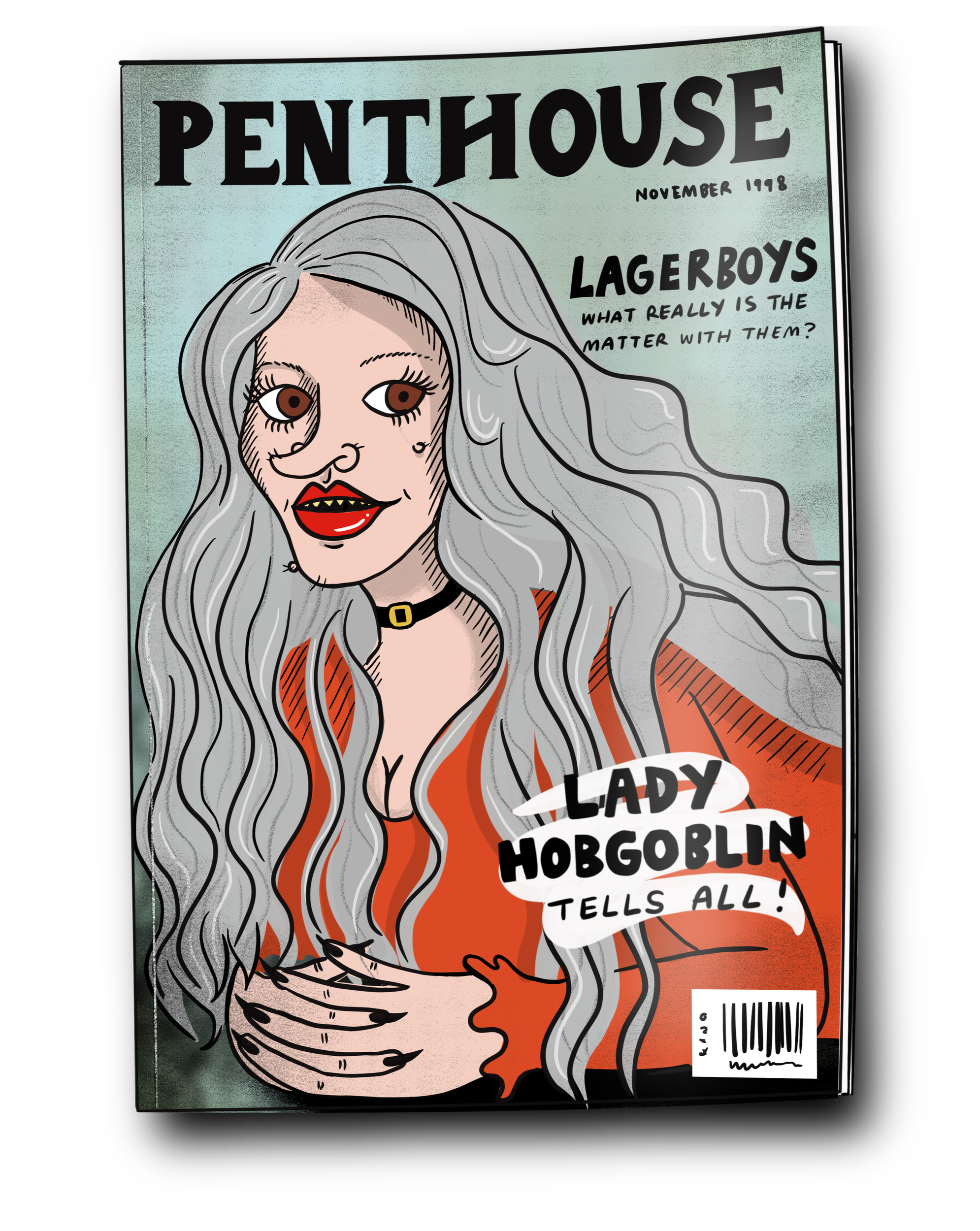

The rise and downfall of Wychwood Brewery includes tales that sound as fantastical as the Wychwood Forest itself, including mud-wrestling Hells Angels, full-page Penthouse adverts, and brewery visits from the then Prince—now King—Charles himself.

There are three key elements to untangle in this story—the brewery, the beer, and the pubs. This is how we can understand just how influential Hobgoblin really was, both as a beer and a pub chain.

To begin, I meet Ian Rogers, the man who popularised the beer, exploded its growth, and set up the pub chain. Remarkably, it once boasted 33 sites and was 22nd on the inaugural list of 100 fastest-growing firms in The Times in 2000, gaining an invite to sponsor Richard Branson’s Kidlington house in the process.

Ian knew he wanted to get into the business early. “At 14 years old, I decided I wanted to own a brewery and pub company,” he tells me.

““When you weren’t brewing or sleeping on the malt sacks—getting a bit of kip before the alarm went off—then you were cleaning or filling up casks.””

He had gained business experience at Duracell in the early 1980s. Later, he worked for Bass, where he was given the opportunity to manage pubs, often those serving the Irish community in London. After a few other jobs, he ended up in Oxfordshire working for Halls of Oxford, a pub portfolio that, at the time, was owned by multinational hospitality firm Allied Domecq (at its height, it ran a monopoly of Oxford pubs).

“That’s where I really learned the business,” Ian says. He tells me how rising house prices gave him the capital to invest, after he made three different moves in England’s South East.

In Oxfordshire, Ian was running a brewpub called the Oxford Bakery and Brewhouse. Every week, he would get through some 10 kilderkins (180 gallons) of Glenny Brewery’s Wychwood Best. He soon became one of its biggest customers.

***

When I eventually track down Paddy Glenny, he tells me the story of how he learned brewing in West Germany during the height of the Cold War, at the Schultheiss brewery in Berlin.

Around 1980, before he went into brewing commercially, Paddy was employed in a Mercedes factory in the German capital, and would smuggle photocopier parts behind the iron curtain and into Prague. He did so to help his brother, journalist and McMafia author Misha Glenny, who was part of Charter 77, a pressure group advocating for democratic reform in Czechoslovakia.

Photocopiers—or any device that could provide information to the public—were banned by the Soviet Union, and the only way to keep the machine working was to use contraband parts. “I was able to build special compartments into the cars, and that’s how I spent my spare time in those days,” Paddy says. “The hardest border to cross was into East Germany from West Berlin—sub machine guns [pointed] in your face.”

When Paddy returned to his home in Oxford in the early ’80s, he took out an £18,000 bank loan (close to £70,000 in today’s money) with his mother as guarantor to open a brewery in part of Clinch and Co.’s Witney Eagle maltings, which had been shuttered for a couple of decades. The thin building suited a tower brewery system, and Paddy saved money by using secondhand vessels and doing all the construction, wiring, and plumbing himself.

His first beer was called Eagle Bitter, inspired by the original name of the maltings, but in 1983 he received a cease-and-desist letter from Charles Wells, whose bitter (and brewery) already used the Eagle name. Paddy swiftly changed it to Witney Bitter. He then brewed Wychwood Best after being inspired by Wychwood Forest north of Witney, which had connections with local folklore, including tales of fairies, ghouls and witches.

In addition to selling locally, Glenny exported a 7.7% barleywine, called Little Gem, to Italy, which was brewed with Herefordshire hops and matured in oak casks for 70 days.

In 1985, Paddy employed Chris Moss as a junior partner and taught him brewing. At the time, he says, he was becoming increasingly fed up with Thatcherism, and frustrated at how rural parts of the country were gentrifying.

“I found the miners’ strike very painful to watch, and the A40 was so jammed up with yuppies driving to their second homes in Volvos and Porsches,” Paddy says. “I was in a pretty Tory place.”

He decided to sell the brewery in 1990 and move to British Columbia, Canada, where he set up Nelson Brewing Company.

To buy Paddy out, Ian Rogers sold his five-bedroom house in South Leigh near Witney and a chapel he owned in Somerset, and became a partner with Chris for £85,000 (£165,000 in today’s money). The total included the freehold of the brewery. At the time, he was still working for Halls. “If my bosses had found out, I’d have been sacked,” he says.

Illustrations by Jessica Wild

Ian tells me he worked hard for Halls, insisting those early years with Glenny were a “weekend job.” But by coming on as a partner at 28, he had realised his 14-year-old self’s dream.

“It was precarious—we used £80,000 equity to buy the shares, and we now had a 100% mortgage on our family home,” Ian says. “But my wife was a diamond, and she said, ‘Go ahead and fulfill your dream.’”

Once taking on the brewery, Ian continued to sell its beers to the Oxford Bakery and Brewhouse. Within a few weeks, he decided it needed a rebrand. He renamed it Wychwood, after the Best. In 1993, he hired Matt Watts as a drayman, cask cleaner, and rat-catcher who would also help with brewing—then three eight-hour shifts on the eight-barrel system. As the brewery output changed, so did the working conditions.

“When you weren’t brewing or sleeping on the malt sacks—getting a bit of kip before the alarm went off—then you were cleaning or filling up casks,” Matt tells me.

Ian introduced a new range of beers, including Dog’s Bollocks (named for a popular ’90s slang term), and began to sell another of its beers, Hobgoblin, to a wider market.

***

Just like the Wychwood Forest, Hobgolin’s origin is suffused in myth and folklore.

One story originates with the Plough at Kingham, which the brewery supplied. Back then it was a traditional pub frequented mainly by farmers; today it’s a food-led pub that’s popular with “yuppies,” as Paddy would call them. Its then-landlord asked Glenny Brewery to make a strong beer for his daughter’s wedding.

After the nuptials, the remaining beer was supposedly taken to the Grog Shop in Jericho, Oxford, where customers made return visits to refill four-pint vessels. Chris claims to have noticed how quickly the shop sold the 6.5% ruby beer, and that it had renamed the beer from Wedding Ale to Hobgoblin.

This particular version of events was retold to Ian by Chris Moss, who died in 2001, but it’s a myth, according to Paddy. “That whole story is rubbish: I wanted to brew a strong ale for winter,” Paddy says. “I came up with the name—I thought it was a cool name.”

Paddy tells me how he came up with the idea for the logo based on a grotesque hobgoblin, and commissioned artist Andy Farmer to design the pump clips. Later, after taking on the brewery, Ian hired illustrator Ed Org to tweak the original logo. He’d bumped into Ed at a craft fair, where he was impressed by his pen-and ink-drawings. (For his part, Ian says he believes the original was created by a student at the Grog Shop.)

“They were all pieces of art, and Ian’s bottles were way, way ahead of their time,” says James Coyle.

Wherever it originated from, the logo was based on a mythical character that was ugly yet somehow charming, and folkloric but not old-fashioned. In the early 1990s, the Hobgoblin was primed to become the ultimate disrupter. Ed was soon commissioned to work on all the original Wychwood beers—not bad considering it was the first time he had produced work in full colour—which included Fiddler’s Elbow, Circle Master, Black Wych Stout, plus different versions of the Hobgoblin itself.

The illustrations he produced live on today in memes and advertising folklore.

“It was just brilliant when we had it,” Ian tells me. “Now it’s changed and fucked up by corporate people.”

““I thought if I could get Hobgoblin into a bottle I could sell it into supermarkets.””

The brewery grew rapidly, benefiting from the Beer Orders, which meant it was easier to get independent cask in pubs. Before 1989, six major brewers dominated the market; they owned thousands of tied pubs, which effectively blocked smaller rivals from selling their beer to customers. The solution restricted the number of pubs that could be tied to a brewery and forced guest beers to be sold, much to the benefit of Wychwood and its ilk.

The Hobgoblin logo became popular with wholesalers in the early 1990s, and soon all the Wychwood beers became sought-after in cask. But when it came to supermarkets, traditional beer styles were woefully represented.

“I knew this would change,” Ian says. “I thought if I could get Hobgoblin into a bottle I could sell it into [supermarkets].”

The brewery became the first to produce a bottle with a pictorial label—there were not yet pictures of abbots on Abbot Ale, or the landlord on Timothy Taylor’s Landlord. Instead, the design of the era focused primarily on typography. Ian built on Ed’s work by hiring artist Dave Noonan to add the “Hobgoblin” lettering and adapt it so it met export regulations.

Off-licence chain Unwins was impressed. Then, Ian pitched Tesco. “They had never met anyone like me,” he laughs. “They had only dealt with national brewers and they knew that in America beer was the next big thing.”

Without necessarily using the word in pitches, Ian was positioning Hobgoblin as what we might refer to today as “craft.” He wanted to cast Wychwood in opposition to more traditional breweries like Greene King. It was more akin to the British version of San Francisco’s Anchor Brewing Company—which is somewhat ironic, considering the latter was founded in 1896.

When developing the look of the bottle, Ian also noted that most beer labels were made cheaply, likely at the behest of accountants. Instead he went to a labelling firm demanding gold embossing, gold foil, and the Hobgoblin in full colour, even though it would cost 10 times more than his big-name rivals. “They were like, ‘It will cost you 0.1p instead of 0.01p,’ and I said, ‘I don’t give a fuck,’” Ian says.

It was a small cost, relatively speaking. In the early ’90s, a beer like Hobgoblin would sell for around 75p. Ian never spent anything on advertising, while the likes of Morland were running ads in the Times and Telegraph. He then went to United Glass to commission a curvy, Coke-shaped bottle that was flint (clear), undaunted by the risk of the beer becoming light-struck. He believed they would sell so quickly that off-flavours wouldn’t occur.

Hobgoblin became the fifth best-selling bottled beer in the U.K., outselling legacy brands like Newcastle Brown Ale. One Nielsen ad-man even admitted to Ian that every major brewery was furious at being outsold.

“We went through the roof and were in every supermarket within a year,” Ian says.

Drinkers could also send in six bottle tops and a postal order of £2.50 for a T-shirt, resulting in thousands being dispatched weekly. I remember them being ubiquitous at Glastonbury in the mid-1990s. At GBBF one year, Ian claims that 10% of visitors were wearing Hobgoblin merchandise.

“We were getting photos every week of Hobgoblins tattooed on legs, arms and backs,” James says.

Penthouse even ran a free full-page advert for Dog’s Bollocks. Ian says he’s still baffled to this day as to why they gifted him the free publicity. At Halloween, a flashing pump clip was produced and given to pubs if they bought two firkins—James claims that 5,000 pubs took them up on the offer. A Three Lions beer to coincide with Euro 1996 drew the wrath of the FA, and in the process gained more free publicity.

Hobgoblin’s next step was cracking the U.S. market that Ian revered. Using importer Eurobubblies, he sent a 40-foot container three times a year. He then recommended other British breweries, such as Black Sheep in Yorkshire and St. Peter’s in Suffolk, which took advantage of this newly created export demand.

Then they launched in Canada. Then Japan.

“We couldn’t keep up,” Ian says of the growing demand. He appointed a head brewer called Jeremy Moss—no relation to Chris—but the real answer was to move production to Marston’s in Burton-upon-Trent after Ian met James in 1995, and appointed him sales director. The Witney brewery could produce a maximum of 30,000 barrels a year and at its peak, in 2016, Marston’s produced 100,000 barrels of Hobgoblin.

“My first signing for Marston’s was to represent Hobgoblin and the Wychwood portfolio,” James says. “Ian owed the IP but we brewed it, paid for everything and paid him a licensing fee.”

Ian expected drinkers to complain that the beer tasted different, but despite the cultish following, no one seemed to notice. In fact, Ian admits, he wasn’t the biggest Hobgoblin fan, and wanted it to taste more like his favourite drink, Timothy Taylor’s Landlord. To appease him, the brewers said they would evolve it to be more like the pale ale. At each brewers’ meeting, they told him that it was slowly being tweaked.

“When I sold the company a few years later, they told me they never changed a thing,” Ian says.

***

“The average Hobgoblin drinker were weekend warriors who worked in IT and finance and had tattoos under their sleeves,” James tells me. “The pubs created—without being articulated—an environment that was inclusive, that allowed people to be themselves.”

Ian wanted to emulate what David Bruce had achieved with his Firkin chain, but with a few tweaks, as he believed their beer often varied in quality. “Sometimes the beer would be good, but you’d go into another [pub] and the beer was undrinkable,” he says.

Still, he liked the student feel, vintage wooden furniture, and “not exactly sawdust” but certainly a pared-back aesthetic. While everyone was playing chart music, he dreamed of the Chili Peppers, Nirvana, and Radiohead. “I wanted young people, but I didn’t want Magaluf. I was going for a different, more educated type of young person,” he says. “One listening to the type of music I liked.”

Ian contacted accounting and consulting firm Touche Ross (now Deloitte), which put him in touch with Paul Adams, then the finance director at the Firkin Pubs. He offered Paul the opportunity to be the accountant for the pub venture to help with investment, and rein in excesses.

“I needed someone to keep figures in hand, and Paul needed someone entrepreneurial,” Ian says. “I knew I was going to grow a company from quite small to quite large, and Chris was a lovely man but not really entrepreneurial.”

They approached U.K. tenanted pub portfolio Inntrepreneur, and in the summer of 1992, took over two pubs, The Clarence—which I visited in Staines with my dad—and the Three Horseshoes on High Wycombe high street.

Arranging free-of-tie cask lines was vital, which Ian again describes in terms that are reminiscent of the “craft” of today. Such beer was what young people wanted to drink in the early 1990s, he says, but offering fair access to market wasn’t supported by a lot of chains.

The Staines pub was the first official Hobgoblin, opening on November 5th, 1992. In its previous form, the pub was making less than £2,000 each week. Ian mimics a rocket noise to describe how footfall exploded, with takings ballooning to more than £9,000 a week. After it opened in spring 1993, the High Wycombe branch became the busiest pub in town, going from £500 a week in takings to almost £11,000.

“They were tired pubs that we took over, but they had to be located near students,” Ian says. “Inntrepreneur were really happy, because we were buying a lot more beer. Anybody who went into these pubs fucking loved them.”

Within two years, they had added Brighton—which is still called a Hobgoblin to this day—Maidenhead, and Bath. Reading, and three pubs in Bristol, soon followed. One pub in Bristol was so popular on opening that the police had to be called because so many customers were spilling into the road that buses couldn’t pass. “That was the hype we’d got,” Ian says.

In 1994, Ian and Paul gave presentations to three private equity firms, opting to partner with 3i. They stayed with them for nine years. The brewery and pub business were expanding rapidly every year, gaining several funding rounds for a 40% share in what became the Hobgoblin Group. (PE normally exits hospitality firms within five to seven years.)

By the turn of the 21st century, this level of funding—£3.3 million over three rounds—led to a portfolio of about 33 pubs and a turnover of £30 million. When Ian first took on the company, it had a turnover of £100,000.

““The average Hobgoblin drinker were weekend warriors who worked in IT and finance and had tattoos under their sleeves.””

Ian employed Paul Carey—“a real Mensa head”—to train and empower publicans to run the pubs their way, and the company offered substantial perks that fostered staff bonding. One was to copy the British gameshow Don’t Forget Your Toothbrush, through which publicans could win a holiday.

“Hobgoblin pubs were just immense fun, and it was important that security guards on the doors allowed people to have fun,” Matt Watts tells me. “Paul was called Scarey Carey for a reason—he kept the mavericks in check by making sure banking, cash, and stocks were always checked.”

But not all of the pubs were successful. Those in less affluent areas, devoid of students, struggled. Glen (who requested we didn’t publish his full name) ran a few of the pubs for Ian, including Forest Hill, in 1995, and tells me that it was a huge cultural shock going from managing a Hobgoblin in Bristol to South London.

The problems were so considerable—including break-ins and a nearby pub being fire-bombed—that he had to employ the Hells Angels as door staff to keep order. Members of the motorcycle club were already working at the Hobgoblin (briefly The George Canning, now The Hootananny) in Brixton, where Ian tells me they would organise mud-wrestling matches in the pub.

“Once they were doing the doors, the problems stopped—you wouldn’t really mess with those guys,” he tells me.

The pub became an established rock music venue, booking acts like tribute band Think Floyd. Glen says he loved working for the pub company, even earning a one-night stay at the Ritz during one of the gameshow nights. But some of the acquisitions were tricky to stamp the Hobgoblin brand on, especially the 11 acquired from Henley Taverns, which included the one in Forest Hill, South London.

Glen believes that the change from grants to student loans meant that younger people shifted into different consumer habits that have since become hallmarks of the early 2000s. Instead of going to the pub, they would go shopping or clubbing instead.

“The whole market changed, and students went from grungy and listening to Alanis Morissette to having designer clothes,” Glen says. “These newer pubs were smart, almost clubby. It diluted the identity, but they were changing with the times.”

By 2000, Hobgoblin continued to acquire larger city-centre pubs like Qube in Millennium Square, Leeds, which had variable success. One account in the local CAMRA newsletter suggested that the unisex hand-washing area was the most popular area for customers to socialise.

Wychwood even started making a range of alcopops—including one called Beelzebub—designed to appeal to mainstream drinkers. Oddly, these had a big export market, with up to a quarter of the stock sent to Thailand. Ian admits larger venues like Qube were difficult to manage. Eventually, it was sold on to JD Wetherspoon, which re-opened the venue in 2007.

Wetherspoon’s rise at the turn of the century paralleled the Hobgoblin pub chain’s decline. In 2001, the nationwide chain became the fastest-growing company in the U.K., opening its 500th pub as it acquired or opened more venues each year, until its own peak in 2015.

Understanding that he’d have to cut costs to compete with the discount chain, Ian decided in 2001 to sell both the brewery and the pub chain for £2.25 million and £9m respectively. He believes the brand alone is now worth £100m.

“I was burnt out,” he tells me.

James admits there weren’t many takers when they tried to sell the whole business, hence the decision to split the pubs and brewery. Hospitality company Balaclava acquired the pubs, and Refresh, run by Rupert Thompson—now the director of Hogs Back Brewery in Tongham, Surrey, and the person responsible for the Old Speckled Hen adverts—purchased Wychwood.

Depressingly, both Balaclava and the U.K.-based pubs all folded within 15 months. Strangely, however, their legacy lives on, as those that operate in Japan continue to thrive.

Ian met Mark Spencer—who emigrated from England to Japan in 1986—on an EU trade mission about 25 years ago. Mark tasted Wychwood beer for the first time, was shown a brochure, and decided to recreate the Bicester branch of Hobgoblin in Tokyo, brick-by-brick.

He ordered nine pallets of Wychwood beer by borrowing a liquor licence, closed his Spanish-themed restaurant, and started looking for a pub to take over. When he found one in the Tokyo district of Akasaka, Ian sent him another container, but this time filled with Hobgoblin mirrors, tables and chairs.

“It was packed from day one—like a London pub,” Mark says.

In 2002, he opened another, larger Hobgoblin pub in Roppongi, which still stands today. During sporting events he has to charge entry to manage capacity, and can have up to 700 people visit per day. Mark even made sure that one of the beers at the British pavilion at this year’s World Expo in Osaka was Hobgoblin IPA.

Mark admits the Roppongi Hobgoblin is like a Wychwood museum. In the toilets you can see 20 or more photos of all the pubs from Reading to Brighton. Friends of mine who visited in 2019 felt somewhat discombobulated, stepping into a British pub the day after they landed in Japan and seeing the likes of bangers and mash and fish and chips on the menu.

“It baffles a few people, but you’ll love Roppongi—it’s like the old Hobgoblin pubs,” he tells me. “Nothing has changed.”

***

Speaking to me from beneath the gaze of a portrait of former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, at Manor Farm in Surrey, Rupert Thompson seems an unlikely one-time custodian of Hobgoblin, having heard the stories of Penthouse, mud-wrestling, and Hells Angels.

But he is steeped in the history of beers familiar to households up and down the country. Before he acquired the Wychwood portfolio of beers, cider, and alcopops, he was brand director at Carling, and had persuaded his bosses to sponsor the Premier League with a £20 million advertising spend.

He joined the board at Morland and focused on Old Speckled Hen, relaunching it in a clear 500ml bottle in 1993, and using a small ad agency for the advertising campaign. “Ian did really well with Hobgoblin bottles, but I think it was sparked off by Speckled Hen, which kickstarted the premium bottle sector,” Rupert tells me.

Refresh already owned beers such as Manns Brown Ale, plus the licensing rights to Löwenbräu. When James mentioned to him that Hobgoblin was for sale, Rupert swooped for Wychwood—plus another brand, Brakspear—and made James his right-hand man within the burgeoning drinks firm.

The purchase included Dog’s Bollocks. Rupert tells me an amusing tale about how he once showed the then Prince (now King) Charles around the brewery, and says he smiled when he saw the sign advertising the strong golden ale.

Of all the brands he’d acquired, it was the Wychwood alcopop that drew Rupert’s ire. “The first thing we did was sell it to LWC Drinks,” he says. “We decided to focus on Hobgoblin above others and build on what Ian and James achieved.” Also sold was the Green Goblin cider brand, which went to Thatchers.

Around the same time, Rupert began workshopping some Hobgoblin campaigns. When speaking to creatives, he’d jokingly refer to brands he’d formerly worked with, such as Carling, as the “Lagerboys.” The creatives took the word and built it into a line: “What’s the matter, Lagerboy—afraid you might taste something?” The initial ad spend was £150,000.

“You sometimes get a nugget. This insight was people felt they were being advertised to all the time by lager and there were no ale adverts,” Rupert says. “And that the beers that had more flavour and taste were being squeezed out by the marketeers.

“It was one of the first campaigns that went viral, before there was such a thing as viral marketing, because everyone was repeating it, and they still do to this day.”

““Hobgoblin pubs were just immense fun and it was important that security guards on the doors allowed people to have fun,” ”

For all the adverts’ ubiquity—then and now—it’s quite staggering to think that they ran mainly in the trade press. Rupert believes their success was only achievable outside of bigger companies, where creative agencies compartmentalise each aspect of the marketing of a beer. With Lagerboy, he could control the whole idea.

“I had had advertising campaigns that didn’t work, but luckily I made all those mistakes at the expense of other people when I was working for them,” Rupert says. “It also worked because the ugly Hobgoblin was saying it, and he became the brand spokesman.”

In terms of sales, it was perhaps the last nationwide successful cask ale advertising campaign that resonated outside the beer bubble—the Bombardier advert starring late comedian Rik Mayall was memorable, but it didn’t land the same way, maybe because Hobgoblin already had a cult identity.

Rupert then positioned Hobgoblin “as the unofficial beer of Halloween,” and ran another campaign to coincide with the Great British Beer Festival, which used the line “Le Real Ale, Because You’re Worth It.”

In 2010, following a G20 meeting in Toronto, then-PM David Cameron—whose constituency was in Witney—gifted U.S. president Barack Obama a case of Hobgoblin beers in exchange for some Goose Island 312 wheat ale from the US president’s hometown of Chicago.

“I think it was [David] Cameron’s idea, and he had visited the brewery a few times,” Rupert says. “It was great PR, but you rarely see an immediate jump in sales. The possible exception was Madonna saying she enjoyed Timothy Taylor’s Landlord.”

Refresh’s goal was to ultimately sell the brewery, eventually agreeing to a deal with Marston’s in April 2008. Rupert says he believed they would be a better custodian of the beer than Greene King were when they bought Morland Brewery in 2000.

“One couldn’t have anticipated they would’ve [eventually] sold to Carlsberg, and I wouldn’t have wanted it to go to them because I don’t think they care enough,” he says. “If I was younger I’d love to go back and revive it, because I know I could, but I’ve done my time.”

“It was all my initiation, and when Refresh took over they took my name out, putting Chris Moss as the founder,” Ian says. “That’s why, when you Google ‘Hobgoblin,’ my name doesn’t come up.”

***

On Facebook, there’s a page called the Wychwood Brewery Memorial Society. The 9,000 or so members post nostalgically about Hobgoblin—a beer now brewed in Burton-upon-Trent after the Witney brewery was closed in 2023.

A lot of comments are about how the beer’s flavour has diminished. After finding it on cask while visiting the Blacksmith’s Arms in Hartlepool, I would be hard-pressed to recommend it, especially when compared to the pint of Camerons Strongarm I had afterwards.

But Hobgoblin’s story isn’t all doom and gloom. Up until very recently, Hobgoblin Gold was one of the best-selling beers in Paraguay, with one container sent there a month during its 2019 peak. “It’s such a hot country that we worked out that beer could work really well in our market,” says importer Josema Gonzalez, who also plays in local metal band KUAZAR.

They were selling tens of thousands of bottles of “traditional” English ale each month, mainly to Brazilian middle-class “hopheads” who would drive over the border for cheaper beer. He even ensured that Hobgoblin sponsored the New York City metal band Anthrax in 2017, with festival-goers recreating those 1990s Glastonbury days by necking the former-Wychwood beer in the mosh pit.

Sadly, Josema stopped importing the beer when the current owners forced him to buy through a third-party, and all those sales to a younger crowd eventually vanished.

It does feel like the end of the road for a brand with such a storied history—an underdog that managed to become one of the most popular beers in the U.K., not to mention a small but one-time successful pub chain. For Hobgoblin there will be no blaze of glory, just a slow fade to black.

While older drinkers might remember Hobgoblin’s famous character and the tagline it eventually adopted, perhaps its legacy is the kind of behaviour it went on to inspire. Back when it was a plucky, independent underdog, BrewDog built its reputation—for better or worse—using viral marketing and publicity stunts.

But if you ever happen to come across an old bottle of Hobgoblin, you might be surprised to notice it has the words “Fiercely Independent” embossed at its base—the same slogan that would one day become the tagline of the Scottish brewery and pub chain. Funny how the best ideas are never quite as original as they might seem.

“That was my design,” Ian says. “I reckon they were fans like you, David, and we were the only ones doing something different.”